“The Rhythms of Inhabiting a Non-Place”

Nilo Couret (University of Michigan)

Gianfranco Rosi’s Fuocoammare (2016) depicts life in the fishing community of Lampedusa, a spiritual successor to the Sicilian village of Visconti’s La terra trema (1948). For Rosi, however, Lampedusa is less the repository of a national popular than it is a front line in the migrant crisis that began in earnest in early 2011 after the Arab Spring. Shooting for the film happened over an 18-month period on the small Italian island only 70km off the coast of Africa in the months before the EU burden-sharing agreement of 2015, a year when over 1 million migrants crossed into Europe.

The ideas of both “migrant” and “crisis” open onto two problems for the documentary filmmaker. The first pertains to the temporality of crisis. Caught between the time of catastrophe and information that structures televisual time and journalistic news cycles, the ongoingness of crisis resists classical narration. Much like the radio news broadcast in the film constantly cambiando argomento , or changing the subject, the duration of crisis is ultimately assimilated as ongoing spectacle. Second, migration posits a problem of a spatial order – where do we narrate from? Conventional depictions of forced migration often take one of two approaches: either following the journey of the migrant and capitalizing on a built-in, linear trajectory; or, presenting the social problem in a Griersonian mode of social reform and investigation. The former organizes events from the position of the immigrant and the latter explains the question from the vantage of the receiving country. Confronted with these possibilities, Gianfranco Rosi’s film rejects both models. In an interview at the 2016 Berlin Film Festival, Rosi explained that in lieu of the investigative documentary found on National Geographic or the docutainment of Michael Moore, his work produces a “space of poetry.”

This concern with producing space differently is characteristic of Rosi’s documentary work. Rosi’s first critical success, Sacro GRA (2013), is a city film that avoids the symphonic structure and the tourist gaze of its predecessors by providing a loose tableau of the Grande Raccordo Annulare (GRA), the ring-road highway that loops around Rome. Rosi produces a habitat through the strada’s inhabitants in a mode reminiscent and elaborated in Fuocoammare. His characters never quite become representative types, as Rosi alternates intimate domestic scenes with impressive landscape shots and organizes events in an order of suggested (if impossible) chronological succession with no narration and few explanatory devices. Both the highway and the island imply a certain finitude that lends itself to representation – the former encloses the city, the latter is an enclosed space – but Rosi’s space of poetry is one that explores life in a space that cannot become place.

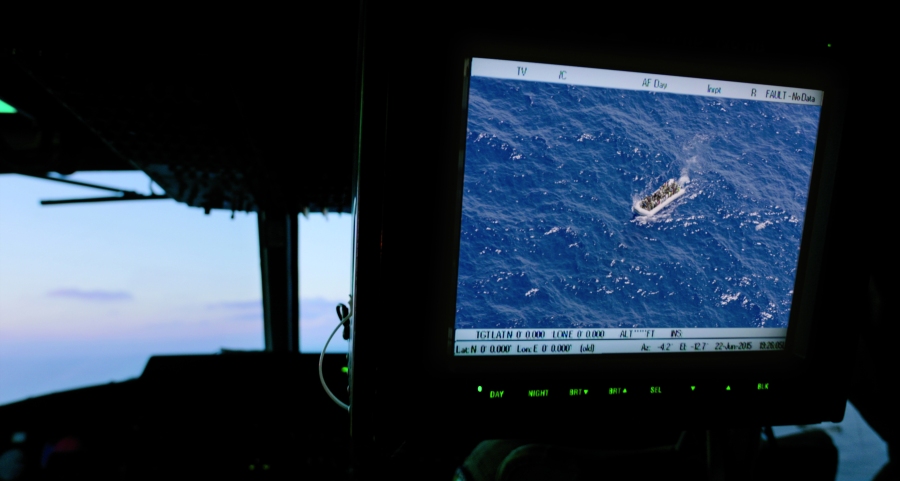

If the GRA is a limit that no longer delimits, Lampedusa is an inhabited no man’s land. Rosi constructs this peculiar space by intercalating scenes of the fishing community with scenes of the migrants’ rescue. One might expect these scenes to coordinate parallel structures or eventually to intersect – either would organize these spaces in relation to the other. But Rosi’s space of poetry does not abide by such a logic. The scenes of the fishing community depict several months in the life of a young boy, Samuele, at school, at play, and at home. The migrants’ arrival is represented through a series of discrete rescue operations, each getting us closer to the migrants’ vessel. The duration and rhythms of the fishing work offer counterpoint to the gradual and staggered presentation of the latter.

The fishing community is cobbled together in ways reminiscent to Rosi’s earlier work, with everyday scenes loosely related through suggested temporal succession or spatial continuity. We watch Samuele’s father catching squid on his boat, Samuele’s nonna making a calamari sauce, then the family sharing their dinner. The local DJ plays the requests made by the island’s inhabitants and a sound bridge connects his cabin to his listeners’ kitchens. This shaggy continuity produces a habitat from these daily habits, with Samuele an ideal ‘protagonist’ precisely because of the way puberty is so much about the body habituating itself to its dimensions. In fact, we follow the passage of time in the later Samuele scenes precisely through his treatment for amblyopia, his eye patch forcing the child to habituate himself to seeing in depth.

These sound bridges are almost entirely absent from the rescue sequences, with more close-miked shortwave radio, mechanic droning ambient sounds, hard sound cuts, and abrupt shot transitions. Rosi introduces the migrant crisis with an interrupted mayday and a roving searchlight. Every following interaction with the migrants brings us closer to them but carefully withholds key beats in the rescue operation narrative: the encounter, the arrival, the bureaucratic processing, the medical treatment, the autopsies. There are few moments of migrants sharing their stories in front of the camera: a late interview explaining the tiered hierarchy on the overcrowded boat and an earlier performance of a song in an episode that interrupts the most routine moments of bureaucratic operation. The film takes this cue, using the migrants’ plight as a disrhythmic element.

Of course, this disrhythmia opens onto several ethical questions, especially with a film that culminates with three disquieting shots of migrants’ dead bodies before returning to Samuele on the docks at dusk. We could fault the film for using Samuele as ‘protagonist’ but I want to suggest that it is precisely in this juxtaposition of “rhythms of inhabiting” that the film registers the “migration crisis” anew. Well before this conclusion, other sequences already punctuate the texture of this habitat: the returned gaze of a migrant in close up from behind a window, the migrants standing before Rosi’s camera as they do the official cameras of bureaucratic record, and the camera’s presence on a boat with limited capacity that retrieves dehydrated migrants who collapse at the cameraman’s feet. These moments disquiet precisely because the film neither demarcates spaces nor clarifies the relations between spaces, inviting us to ponder where we are (or can be) in relation to these spaces. We wait for these spaces to converge – will the diver happen on a sunken body? will the child flash his light on a refugee during his nocturnal hunting? – but this is a space that cannot be the sum of its parts. Rosi leaves us adrift, like the culminating, near point of view of the swaying horizon from atop the migrants’ boat or the final shot of a playing Samuele on the swaying docks. Echoing Marc Augé’s discussion of the refugee camp as a non-place, the film’s own space of poetry offers us a space that also cannot become place.

“A Sea Divided”

Linnéa Hussein (New York University)

Many media outlets have described Gianfranco Rosi’s Fire at Sea as a metaphor for modern-day Europe. On the one side, the old world of Lampedusa is intact: boys are playing, a grandma is cooking pasta, and tranquility has not been disturbed. But, on the other side, fires are burning. Devastating images show young men fighting dehydration, aid workers sorting body bags, as well as forty dead bodies amidst the garbage at the bottom of a boat, where there had been just enough space for these migrants to suffocate. Rosi’s filmmaking practices seemingly find refuge in old myths that divide the world into us and them. While the metaphorical reading of the juxtaposition of the idyllic and the horrific might allow us to see Rosi’s film as an ethnography of a crisis and not of a people, it is worth investigating the politics of representation that sometimes get buried underneath discussions of film form.

Fire at Sea invokes discomfort, at least in this viewer, as it is a painful reminder that the old Flaherty tradition of cinematically distancing Westerners from Others is resurfacing at a time when Europe’s conservatives already try their best to defame Arabs and Africans. As a German-Iraqi myself, I am implicated in the “us” as well as the “them.” So much work is demanded right now to prove that integration can be possible and that not all immigrants are victims or savages. In times like these, when alienating circumstances are already at work, Rosi films Italians as fully-fledged characters in opposition to nameless migrants, who only become visible through the gold heat foils wrapped around their bodies, and who stare into the camera, mute, and without being given the option to consent to the image-making.

A salient example of this is an unnamed Muslim woman, who is asked by the authorities to loosen up her hijab to show some hair for identification purposes. Bill Nichols argues in Representing Reality, that representation of certain disasters “licenses empathy and charity, if we see past the absent presence of the expository filmmaker (…) whose lack of response provides the occasion of our own” (91). One way of reading this scene could credit Rosi for privileging the recording of the woman’s powerlessness in an effort to raise awareness about helpless people like her. But, another way of reading implicates him in that woman’s heighted anxiety about showing her hair in the first place. His presence – as a male and as a cameraman – exacerbates this violation of privacy, which ultimately increases the spectator’s discomfort as it situates the audience as involuntary voyeur.

In another scene, where the intention might have been to give migrants a voice of their own, the camera closely observes a group of Nigerian migrants chanting in prayer. This is one of the few moments when non-Italian voices can be heard, and yet, while the accounts of horror reflected in the content of the prayer – rape, killings, ISIS in Libya, and drinking urine in the Sahara Desert – might have been included to elicit sympathy, its foreign form of chanting simultaneously establishes a distance between the African men and the Europeans. One might go as far as to say that it makes one recall the image of the “noble savage,” wise and yet unable to converse like his European counterpart. As a result, difference between Europeans and Others is constantly reinforced, which ironically echoes conservative European fears posed in the question: Are these people capable of integration or are they just too different?

Any documentary filmmaker present in this situation is faced with a precarious choice: to record powerless people in their most vulnerable state or to turn the camera off, in which case no one will ever witness their suffering. A different approach, as in BBC 2’s Exodus, another recent documentary about the crisis, is to give migrants cellphone cameras to record their own journey. While the end product in Exodus still reflects the institution’s editing practices, seeing people on boats interact with one another, sending GPS locations to friends in the US via Whatsapp and the like, makes the people on boats seem more three dimensional to Western audiences, and fosters a possible imagination of integration.

Rosi’s film showcases the problem of documenting an ongoing crisis and a society that seems to vacillate between Willkommenskultur (culture of welcoming) and xenophobia. While the architecture of Lampedusa – the remoteness of the camp from the places where the Italians live – might suggest a physical and therefore social divide, one also has to take into consideration that keeping the two localities divided on screen is a conscious choice to create a disconnect that suggests that Europe has no accountability in creating the crisis. Even before Lampedusa became a refuge, idyllic Europe was an implicit player in colonial as well as post-colonial exploitation of the regions people are fleeing from today.

Rosi’s film, as A.O. Scott writes, doesn’t raise awareness but “cultivates alertness.” To come back to Nichols, Rosi’s silent witnessing certainly allows for an occasion to be charitable. His images do show us in Europe and elsewhere the fire at sea that we often miss when we only pay attention to the changing demographics in our own city centers. The film does not, however, strive to show us any commonalities between Arab or African and European life. By invoking conservative ethnography traditions that exoticize Others, one has to wonder if Rosi’s filmmaking practices are a wider metaphor not just for Europe but for the time we live in.

Each time I have watched “Fire at Sea” I was left with the sensation that in making it Rosi has been more preoccupied to develop a “poetic” documentary than to actually tackle the immigrant’s crisis. Indeed, not only the actual crisis hardly even finds space on screen, but the film is mostly “artificial” in its construction and “empty” narrative-wise . Emblematic of where Rosi’s preoccupation actually lies and of the “emptiness” of his film is the sequence in which we see the doctor checking the children’s eyesight. This is clearly an enacted scene that has no actual function other than that of paying homage to Joshua Oppenheimer’s “The Look of Silence”.

LikeLike

Rosi’s film is full of aesthetism and it lacks of any comprhension of the immigrant’s tragedy. It lingers on collateral charachters as the children and it has no pity for the death of so many innocent people. Beautiful images without heart, images without imagination.

LikeLike