“Chinese Working-class Youth Culture and Mobile Phone Aesthetics”

Jia Tan (The Chinese University of Hong Kong)

When considering youth subcultures in general, few would contemplate them within the working-class context, and the same can be said about the overall understanding of Chinese youth culture. The documentary We Were Smart focuses on a subculture community known as shamate (杀马特), or “SMART,” recognized for their vibrant and extravagant hairstyles, as well as their sporty fashion sense. What sets this documentary apart is its emphasis on working-class youth, a demographic that has been overlooked in existing documentary films and the broader landscape of Chinese youth cultures.

Since the emergence of the New Documentary Film Movement in China during the 1990s, there has been consistent attention focused on the plight of migrant workers within the People’s Republic of China. This issue has also gained widespread coverage through mainstream television journalism and documentary productions. Millions of these workers are employed in factories and sweatshops located in coastal regions of China, and they have played a significant role in establishing China as a global manufacturing hub. Typically hailing from rural areas or small towns, many of these workers migrate to major cities and surrounding areas to seek employment in factories. Prominent works from the New Documentary Film Movement, such as Houjie Township (Zhou Hao, 2002) and Last Train Home (Fan Lixin, 2009), depict migrant workers as socially marginalized individuals. Similarly, the documentary China Blue produced by PBS in 2007 captures the stories of migrant workers involved in the production of jeans for the global market. These portrayals often depict migrant workers as wearing affordable clothing without any association with fashion or style.

We Were Smart uncovers the work and living conditions of shamates, individuals who identify with the SMART style. Alongside the current association of the SMART style with punk, gothic, or Japanese visual styles on the Chinese Internet, shamates use their hairstyles, clothing, internet emojis, and group activities like roller-skating to convey their identity. However, beneath the fancy surface of style lies much more. Director Li Yifan extensively travelled to over a dozen cities and filmed over 60 interviews with individuals who are currently participating or have previously participated in the SMART culture. Among them is the leader of the SMART culture, referred to as the jiaozhu or godfather in the film. This interviewee provides fascinating insights into the history, development, and semiotics of the SMART style, as well as the subsequent criticisms, ridicule, and online attacks it has faced. What one may not expect to see in a youth subculture documentary is the dehumanizing conditions faced by factory workers who are teenagers and youth. Some shamates initially joined the workforce as underage laborers without proper identification documents, making them a vulnerable group that is systematically exploited.

What adds depth to this documentary is the inclusion of hundreds of short videos shot by factory workers, including shamates, on their mobile phones (Figure 1). This brilliant crowdsourcing concept was proposed by the godfather himself. The director Li Yifan advertised the idea online, paid for these short videos, and skillfully juxtaposed multiple phone screen videos on the screen, which makes this film, in part, a participatory documentary. Additionally, over 900 mobile phone videos collected for this documentary were also shown as a video installation in an art exhibition, allowing the audience more freedom to watch the mobile phone videos captured by ordinary workers.

Accessing factories is no easy task for documentary filmmakers. Even if they are granted entry, they rarely film from the perspective of the workers. It requires significant effort to capture workers on screen in the first place. Thus, the subjective shots from each workstation or work unit on the assembly lines hold immense power (figure 2). They provide first-hand and first-person footage of the inner workings of the factory from the perspective of the workers. As the faces of these workers or shamates behind the camera remain anonymous, what becomes apparent is the repetitive, fast-paced, labor-intensive life within the factory that readily instrumentalizes the workers.

These first-person shots not only capture the essence of the workers’ perspective but also create a unique mobile screen aesthetic through the distinct shape of the mobile phone video itself. The intimate relationship between the workstation and the worker behind the mobile phone camera further enhances this effect. The significant number of video responses submitted online comes as no surprise, considering the widespread use of mobile phones in contemporary China. (Jack Qiu’s book, Working-class Network Society (2009), highlights the extensive mobile phone usage among migrant workers, while Cara Wallis’ Technomobility in China: Young Migrant Women and Mobile Phones (2013) provides valuable insights into young migrant women’s experiences.) Notably, however, in We Were Smart the limited presence of women among the interviewees may indicate the marginalized position of women within this subculture.

Through meticulous efforts spanning years, We Were Smart establishes connections between work and leisure, as well as the production and consumption sectors, which are typically viewed as separate entities. By bridging these gaps, the documentary sheds light on the often-overlooked dimension of class within Chinese youth culture and subcultures. Simultaneously, the film showcases the vibrant and dashing aspects of working-class culture. What unites these elements is the emerging trend of participatory documentary filmmaking and the incorporation of mobile phone aesthetics.

“To Adorno, or not to Adorno?”

Kristof Van den Troost (The Chinese University of Hong Kong)

In the 2000s, a new subculture among young Chinese rural-to-urban migrants emerged. With enormous, brightly colored coiffures and cheap but fashionable clothes, their style suggested an unholy alliance between punk and Japanese anime. Calling themselves shamate 杀马特 (from the English “smart”), these youngsters often had come, in their early teens, from their home village to (illegally) work in the cities’ booming factories. Escaping the numbing, exploitative, and dehumanizing factory work during their very rare days off, they gathered in roller-skating rinks, discos, and parks to have fun within a like-minded community.

In his fifties, director Li Yifan at first sight seems an unlikely person to tell this subculture’s story in We Were Smart (2019). Li’s previous work as a filmmaker dates back to the 2000s, when he produced two award-winning documentaries: Before the Flood (2004) and Chronicle of Longwang: A Year in the Life of a Chinese Village (2009). Part of the then flourishing Chinese independent documentary movement, both films zoom in on the lives of grassroots and marginalized communities in a China then developing at breakneck speed. It is therefore unsurprising that We Were Smart is as much, if not more, about the exploitation of workers, and social injustice in general, as it is about the shamate subculture. In this regard, it rivals Huang Wenhai’s We the Workers, a 2017 documentary on the efforts of labor activists in southern China, as a gripping portrait of the plight of the factory workers that have been so central to China’s economic boom.

One particularly powerful aspect of We Were Smart is Li’s use of footage recorded by the young factory workers themselves on their cellphones. This allows him to vividly document the oppressive conditions of factory work, characterized by various forms of electronic surveillance, security checks, absurd restrictions on bathroom use, and military-style discipline. This footage also includes shocking shots of a work injury and a montage of images showing examples of self-harm to show the physical and psychological impact of the dehumanizing work conditions. In an impressive number of talking head interviews with (former) shamate, we also hear stories of workers being cheated by bosses, of intimidation by hired thugs, and of workers being excluded and discriminated against because of their rural origins.

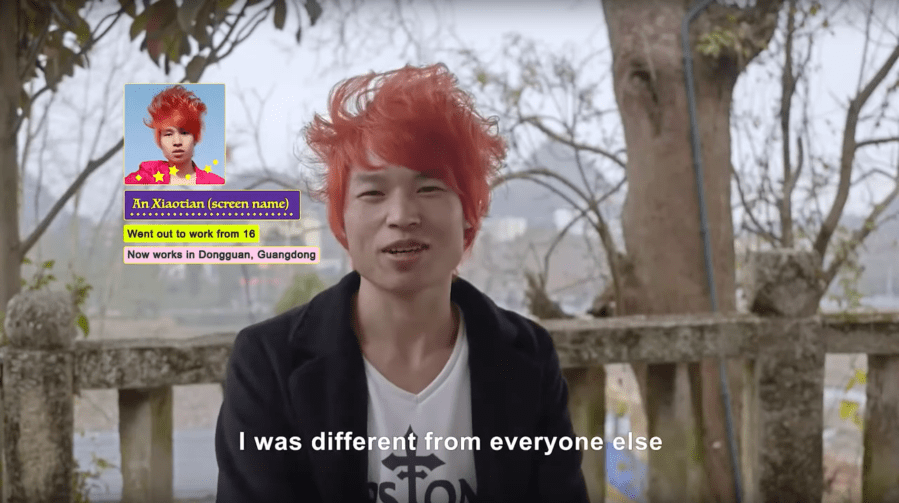

Given Li’s age and his clearly leftist, perhaps even Marxist, preoccupations, one might fear that he would channel Theodor Adorno in his portrait of the shamate, treating this subculture as merely a mind-numbing distraction for the young, exploited laborers, who would be better off spending their energies fighting for their rights. Nothing could be further from the truth: We Were Smart offers a deeply sympathetic portrait of what for many ordinary Chinese is likely a ridiculous, unsettling, or even threatening phenomenon. Stylistically, the documentary does this by adopting something of the shamate aesthetic: occasional intertitles are presented in bright colors and each interviewee is introduced with their online profile picture and nickname, along with details such as the age at which they arrived in the city to find work and what they are doing now.

The interviewees offer several reasons for their attraction to shamate. For many it was a way to protect oneself in an unfamiliar and often hostile urban environment: by blatantly going against convention and looking somewhat dangerous, they were less likely to be bullied or cheated by others. As one of the female interviewees puts it, it was a kind of “porcupine” strategy. For others it was a way to fight loneliness and isolation in the big city: by making themselves look outrageous, they hoped to be noticed, to be talked to, and to be cared for. Adopting the shamate style moreover automatically made them part of a larger community; it offered a sense of family for teenagers often alienated from their real families, as many grew up as “left-behind” children in the countryside while their own parents went to work in the cities. As the film’s use of online nicknames and profile pictures indicates, much of this sense of community was experienced online, on chat services like Tencent’s QQ.

The film’s final third documents the further evolution of the subculture. When shamate became increasingly prominent online in the early 2010s, it gave rise to a backlash, with some of their critics engaging in online violence (bullying, the sabotaging of online communities, etc.) and even real-life threats. In subsequent years, shamate became mostly an online phenomenon, while also undergoing commodification, especially when live-streaming became popular. While this trend allowed several of the interviewees to escape factory life (despite occasional government censorship), it also made shamate lose much of its original grassroots authenticity.

We Were Smart is a masterful documentary, skillfully edited to tell a rich and engaging story of this remarkable subculture. Against common prejudice, Li Yifan clearly wanted his film to put up a defense for shamate as an authentic expression of working-class youth culture in China. Made with the support of a major corporation (Tencent), one may in fact wonder whether Li’s film presents a somewhat sanitized picture of shamate—the film’s young laborers may be unhappy and troubled, but they do not organize themselves to resist and generally just meekly accept their fate. The above-mentioned We the Workers, a more genuinely “underground” production, indicates that this sense of fatalism was certainly not universal among workers. The fact that that film’s director now lives in exile is illustrative of the difficult choices Chinese filmmakers are currently faced with. We Were Smart may be a compromise, but, even if it is, it remains a powerful document of the life of Chinese factory workers in the 2000s and 2010s.