“Dupes and String Pullers”

David Resha (Oxford College of Emory University)

About an hour into Errol Morris’s The Pigeon Tunnel, author David Cornwell tells a story about a boyhood visit to his father in an Exeter prison. Cornwell waves from outside the prison and his father Ronnie waves back. Cornwell, whose pen name is John le Carré, then reveals that his father had disputed this memory and Cornwell agrees that the event never happened. Cornwell continues, “But what’s the truth? What’s memory? We should find another name for the way we see past events that are still alive in us.”

There may be no better quotation that captures Morris’s project as a filmmaker. Morris’s films have always had, at their center, an interest in the relationship between reality and human subjectivity, the latter often mired in misunderstandings and self-delusions.

The Pigeon Tunnel also represents a continuation of Morris’s single interviewee films, in which Morris interviews one individual for the entire film. These films have become quite common in the latter half of Morris’s filmmaking career and include The Fog of War (2003), The Unknown Known (2013), and American Dharma (2018). The single interviewee design provides a distinctive focus for this investigation into subjectivity, but it also raises a question for Morris: how do you make a documentary that examines the ways in which people understand, and sometimes misunderstand, the world in a way that does not cede excessive authority to the only voice in the film?

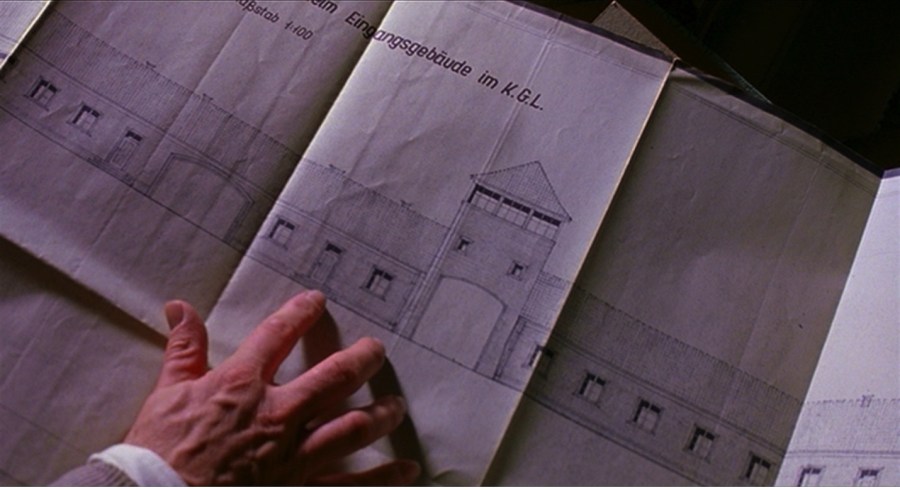

This challenge is illustrated by Mr. Death (1999), Morris’s first attempt to make a single interviewee documentary. When he screened a rough cut of the film to a class at Harvard, there were students “who thought [Fred Leuchter] was right and who seriously started to wonder if the Holocaust ever happened.” Morris then filmed interviews with scholars Robert Jan van Pelt and James Roth to explicitly refute Leuchter’s Holocaust denial claims (see Fig 1).

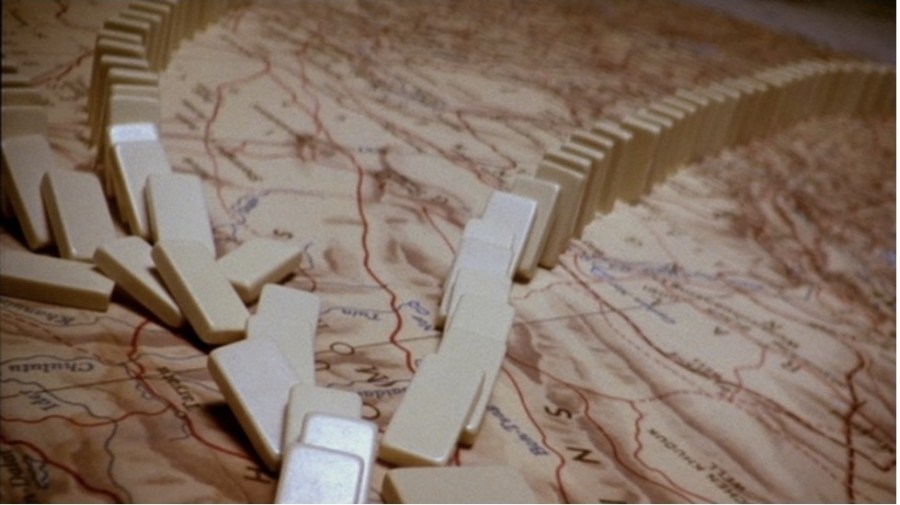

Morris’s subsequent single interviewee films employ various strategies to provide context for and commentary on the interview testimony. These include incorporating repeating visual motifs, like the falling dominos in The Fog of War (see Fig 2), as well as an increased presence of Morris’s own voice, which is all but absent in his earlier films. His voice is especially prevalent in American Dharma, focused on Steve Bannon. In one memorable exchange, Bannon expresses disbelief that Morris voted for Hilary Clinton in 2016, with Morris explaining, “I was afraid of you guys. I still am. I thought she was the best hope of defeating Trump. And Bannon. I did it out of fear.”

Similar strategies are evident in The Pigeon Tunnel. Morris repeatedly returns to visual motifs of pigeons to connect various aspects of Cornwell’s life, including his mother leaving the family, his life as a spy, and the relationship between Cornwell’s writings and his personal life (see Fig 3).

But there is also something meaningfully different about The Pigeon Tunnel compared to Morris’s other films. In a contentious interview for The New York Times Magazine, David Marchese says to Morris that Cornwell “hated interviews and understood them as forums for evasion and self-invention. But in le Carré’s letters, he mentions that you want to work on this film and that he really wants to do it. So when a guy who doesn’t like interviews, understands them as a performance and is a liar says you’re the guy to tell my story, does that raise any questions? Maybe you’re a dupe!”

Marchese is referencing a distinction raised in The Pigeon Tunnel between dupes and string pullers, or “those in control and those controlled by others.” This distinction applies to characters in Cornwell’s stories as well as relationships in Cornwell’s life. But it is also discussed in relation to Cornwell’s interactions with Morris. And the nature of the relationship between Cornwell and Morris provides a framework for the opening of the film, in which Cornwell says about Morris as an interviewer, “I needed to know who I was talking to. Were you a friend across the fire? Were you a stranger on the bus? Who are you? …You need to know something about the ambitions of the people you are talking to.”

This amplification of Morris’s presence, not just as an interlocutor, but as an individual adds an intriguing layer to the film. The act of interviewing is magnified, and we are prompted to ask questions like, “Who is pulling the strings here?” and “Is someone being duped?” Characteristic of an Errol Morris film, these kinds of questions do not have easy or clear answers in The Pigeon Tunnel. But – in contrast to Marchese’s pointed accusation – the interactions between Morris and Cornwell resemble less those of a manipulator and dupe and more an exchange based in respectful interest and curiosity. For example, when discussing the creative process as it relates to real events, Cornwell states, “truth is subjective. …There is some kind of factual record which we’ll never get our hands on.” From his many interviews that touch on the nature of truth and objectivity, Morris has stated again and again that, while it is at times very difficult unearth, he does not believe that truth is subjective. But Morris does not object or critique Cornwell here. He has always been more interested in an open and exploratory interview than an intellectual chess match.

Reviews of Morris’s single interviewee films often express a frustration with the perceived lack of assessment and criticism of his interview subjects. Despite Morris explicitly disagreeing with Steve Bannon, for instance, Owen Gleiberman’s Variety review of American Dharma critiques the film as a “toothless bromance.” The stakes are a bit lower in The Pigeon Tunnel, but several reviewers chide Morris’s insufficient inquiry into Cornwell’s well-publicized marital infidelities. Marchese raises the issue with Morris: “[Is] the material that [Cornwell] wanted to put out into the world…at odds with the film that you wanted to make.” Morris bristles: “[W]hat’s the question for David Cornwell? Did you [expletive] other women? Did you betray your wife? I’m sorry. Get someone else.” Perhaps another way to put it: there is a desire for Morris to pull harder on the strings.

These recurring criticisms about Morris’s more recent films also foreground Morris’s relationship to the current documentary landscape. With the exception of A Brief History of Time (1991), the first half of Morris filmmaking career did not focus on well-known subjects. This changed with Robert McNamara and The Fog of War, and Morris has increasingly interviewed both the famous and infamous. Accompanying that change are expectations about how these figures should be depicted.

Indeed, Morris’s single interviewee films are not a comfortable fit in the contemporary, mostly celebratory biographical documentary genre (e.g., RBG, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, Sly). Morris’s films are neither commemorations nor exposés. They are, rather, open explorations into how his interview subjects understand themselves and the world around them; how they, returning to The Pigeon Tunnel, “see past events that are still alive in us.”

“No One’s Home But Us Pigeons”

Charles Musser (Yale University)

Errol Morris is a one-time private investigator turned filmmaker. David Cornwell (aka John Le Carré), the subject of Morris’ new documentary The Pigeon Tunnel, is a one-time spy turned novelist. During a Q & A, which followed a screening of the film at DOCNYC, Morris radiated intense delight about their conversations which structured this film: he had found a soul mate––someone who shares his more philosophical preoccupations and beliefs.

With Morris seeing Cornwell as a compelling counterpart, I find myself returning to a concept that fascinated Morris in A Brief History of Time: “virtual binaries.” Virtual binaries are “binaries that break apart and potentially collide and annihilate.” Cornwell, for instance, is fascinated by the ways his father, Ronald Cornwell, profoundly shaped his identity––while he considers his mother, who disappeared from his life when he was four, a nonfactor. As Morris pursues that line of inquiry, we might take note that his father died when he was two. Raised by a music teacher mother, Morris retains an abiding passion for playing the cello. Complementary opposites—or what might be called virtual binaries.

The deployment of virtual binaries can be a productive method of interpretation for approaching Morris’ work on multiple levels. For instance, it allows us to better place his documentary work in relation to his work on commercials. As for The Pigeon Tunnel itself? The Fog of War (2003) was Morris’ first film to interview a single individual. In this, it is like The Pigeon Tunnel. Both films hew closely at times to autobiographical reflections by their subjects: Robert McNamara’s In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (Knopf, 1996) and Le Carré’s The Pigeon Tunnel (Penguin, 2016). At other times, the films depart from the books and open new territory. It is worth noting that during the Q & A I attended, Morris playfully suggested that the audience read Le Carré’s book before seeing the movie—something Docalogue afficionados might be in a better position to pursue.

If Morris sees Cornwell as a kind of alter-ego or soulmate, this is not exactly the case with McNamara. Nevertheless, Morris’s curiosity, respect, and even sympathy for McNamara is palpable, and it extended beyond the making of the film. He wanted to understand what made McNamara tick––“who is this man?” McNamara’s belief that the problems of the world could be solved by rationality, by relying on statistics such as kill ratios and body counts, was perhaps his fatal flaw. As Morris has remarked with ironic understatement, that did not work out very well.

While McNamara sought to make the world safe for democracy by firebombing Japan during World War II and then later in his capacity as Secretary of Defense, Cornwell worked at a much lower level as a British spy. Both confronted the Cold War. While McNamara was a true believer, Cornwell’s assessments were far more cynical and ironic––that the United States created the enemies it needed (after Nazism, Communism) even as it created a West German ally that filled its governmental ranks with “ex”-Nazis. Likewise, Cornwell found that, in its approach to foreign policy, the US had no carefully thought out schema, but rather foreign policy decisions were made in the moment. Morris and Cornwell concur: the world is really a chaotic mess. Indeed, McNamara’s account of the Cuban Missile Crisis confirms this.

Morris’s The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography (2016), his only other feature-length film about a “creative,” offers another virtual binary with The Pigeon Tunnel. After all, photography and writing constitute a crucial dialectic in Morris’s psychic imaginary. Faced with total writer’s block, he turned to the camera which takes images automatically. Kodak may have maintained that “you press the button, we do the rest,” but his early films embrace but then necessarily reject that idea––embodied in its motion picture counterpart, cinema verité––through an insistence on stylized lighting, costume schemas and so forth. In an interview about The Thin Blue Line, he even asserted that cinema verité had set back documentary some 20 years. The most unexpected aspect of The B-Side, therefore, is its cinema verité style. Why or how was Morris finally able to embrace it? One way Morris dealt with his post-Standard Operating Procedure (2008) depression, sparked by the documentary’s hostile reception, was to work hard at overcoming his writer’s block. Following his New York Times pieces and books such as A Wilderness of Error (Penguin, 2012), the cinema verité style was no longer so personally fraught; and Morris found useful possibilities in its intimate style. Nevertheless, Morris’s interview styles for that film and for The Pigeon Tunnel are opposites. The B-Side is a warm, affectionate portrait of a portrait maker, who captures what is on her subjects’ surface. She does not try to probe what is underneath, while for Cornwell, surface performance conceals a deeper reality. It is part of the con, of betrayal. Obviously self-reflective enterprises, The Pigeon Tunnel is the A Side to the B-side of Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography.

I would like to consider one more virtual binary, which is crucial to The Pigeon Tunnel and to Morris’s work more generally. This puts the interview, which is Morris’s essential stock in trade, in relation to his concern with truth. For Morris, documentary is about the search for truth and the interview is key in this respect. This has been the case since The Thin Blue Line, the documentary in which Morris exposed the state’s truth––that Randall Adams was guilty of murder––as a lie and offered a new truth in which he identifies the actual murderer, David Harris. Yet most of Morris’s documentaries are explorations that don’t reach such clear-cut conclusions. Many are investigative journeys into the nature of individual personalities. Or, in the case of The Pigeon Tunnel, conversations committed to insights. Late in the film, Morris characterizes Cornwell as “an exquisite poet of self-hatred.” Cornwell agrees and then laughs somewhat nervously. Much earlier in the film, Cornwell wants to know the type of person he is talking to. When Morris demurs––claiming he is not sure he can answer that question. Cornwell then suggests that “we will struggle on and find out who you are.” Although we find out much more about the film’s subject than the man behind the camera, this mutual investigation is in some sense the subject of the resulting film.

There have been moments when Morris seemed to have embraced a definitive method for interviewing his subjects––most notably with the Interrotron, that semi-mystical instrument for eliciting the truth from his subjects. However, a more careful look at his films shows that Morris is constantly reinventing his approach to the interview––and with it, different choices and looks. The Pigeon Tunnel employs a variety of strategies to fragment the interview space in a kaleidoscopic fashion. This is, in part, to emphasize that even when Cornwell claims to be telling us the truth, its veracity is up for grabs. As Cornwell notes, the person being interviewed is a performer and the performance changes depending on the audience. But it also is related to Morris’s long-standing anti-theatrical prejudice. Interestingly, Morris indicated that he was not much of a fan of Le Carré’s many novels (his fictions) and only managed to read one cover to cover (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold). It is Cornwell’s modest collection of nonfiction that he loves. Morris thus creates an approach and a set of formal strategies that are, if you will, the very opposite of The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography.

Lastly it should be said that both Cornwell and Morris imagine active spectators, who are engage their works with inquisitive skepticism. Cornwell notes that almost every one of his novels started off with the same working title––“The Pigeon Tunnel.” He leaves it to the reader to make sense of the metaphor. Morris notes one of the more obvious associations: secret agents such as Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold are like pigeons. These operatives are sent out into the world on their covert missions behind the iron curtain. Many are killed, but those who survive (even those who are “winged” physically, spiritually) return to the home office (their roost), only to be sent out again. But this metaphor may not only apply to spies: like Cornwell, Morris leaves us to speculate as to other associations. Perhaps Morris himself––who launches his films into the world with Q & A’s, often to be attacked and metaphorically killed, sometimes to be winged and sometimes to return to his office with his sense of self intact––lives an analogous life. Might we, the reader-turned-spectator, reflect on our pigeon-like status and embody one further instantiation of this metaphor as well?