“From Telemarketers to Uncouth Comrades”

Stephen Charbonneau (Florida Atlantic University)

The third episode of Telemarketers features a key scene in which our muckraking protagonists – Sam Lipman-Stern and Patrick J. Pespas (Sam and Pat) – finally reach out to a professional journalist, hoping for assistance and guidance. Their contact, Sarah Kleiner, is an established investigative reporter with a track record of shedding light on charity grifts. Considering Sam and Pat are both dogged whistleblowers for the telemarketing industry, she seems like a natural ally. Nevertheless, Sam has concerns. Both he and Pat are former telemarketers and as unpolished as they come. One is a high-school dropout and the other is a previously incarcerated drug addict. In spite of these concerns, they discovered Kleiner was ecstatic about their contributions. “I was giddy,” she exclaims in the scene, “because I had documents; I had the black and white numbers, but you guys had all the stories.” This prompts Pat to respond, “You came at it from one end, we came at it from the other end.”

This single line struck me as a pithy summation of the film’s approach. Telemarketers, a short documentary series released this past August on HBO, tracks a twenty-two-year journey on the part of Sam and Pat through the underbelly of corrupt charity fundraising. Having met as misfit castaways in a shady New Jersey call center – the Civic Development Group (CDG) – both Sam and Pat grow increasingly suspicious that their telemarketing jobs are part of a larger criminal enterprise centered on exploiting the altruistic instincts of regular folk. As such, the series proceeds inductively from within the bowels of the office where Sam and Pat met, literally forged from the former’s YouTube videos documenting workplace helter-skelter. Slowly, but surely, the debauched office culture of CDG is revealed as symptomatic of a deeper systemic sickness. By documenting their experiences in telemarketing as well as their investigation, Telemarketers animates the “documents” and “black and white numbers” possessed by Kleiner. The stories featured here are primarily anchored in a dysfunctional work environment in which the signifiers of professionalism are entirely absent. On the one hand, Sam’s shaky camcorder footage indexes the wild and subterranean sphere of fraudulent fundraising. But eventually we come to realize that the same realm can cultivate a sense of community among disparate and displaced persons. The juxtaposition of past archival video with more recent talking head scenes of the filmmakers’ co-workers repeatedly demonstrates a sense of friendship and camaraderie among the employees. Over the course of its nearly three hours, Telemarketers demonstrates that Kleiner’s documents and facts accrue a hefty anthropological currency as tales “from the other end” embed us in a diverse subculture of the marginalized and forgotten.

This sense of community is conveyed most clearly through a portrait of Sam and Pat’s friendship. While this relationship is bound up with a broader collective of telemarketers – a diverse assemblage of teachers looking for extra income, high school dropouts, and people with justice history – the film is ultimately a portrayal of a bond between two co-workers who find meaning within the madness of their environment. As previously stated, the narrative arc of Telemarketers covers decades and includes periods where Sam and Pat have concluded that their story has ended, only to discover that new questions need to be answered. For instance, approximately halfway through the series, CDG is forced to shutter over findings that it was violating the law and misleading contributors. Both Pat and Sam assume that justice has been served and they can move on with their lives. However, they soon realize that executives were given a slap on the wrist and have persisted in charity fraud, only under a new name. While the two pals resume their investigation, the sense of exhilaration is less about the answers they will find or the possibility of redressing these wrongs. Rather, the constant interruptions of their decades-long endeavor are always bolstered by a feeling of getting the band back together.

This speaks to the film’s strengths, weaknesses, as well as its blend of comedy and melancholia. The warmth of Pat and Sam’s friendship is only surpassed by scenes featuring Pat’s wife, Sue. The specific scenes of Pat caring for Sue in the wake of her struggles with cancer are among the most moving in the whole film. In fact, the film suggests Pat’s personality draws people out of their shells, nurturing a sense of community in the process when he returns home at one point and neighbors are shown leaning out their apartment windows calling out to him. The film’s rootedness in such moments of companionship render its social justice ambitions both admirable and comic. There is clearly educational value in this series, and Pat and Sam’s discovery that the police unions were, in fact, co-conspirators of these telemarketing scandals is genuinely eye-opening. In this manner, the film is – to a substantial degree – a portrait of a police state where the victims of policing are inadvertently advancing the interests of a corrupt system. Scenes of former prisoners working as telemarketers and mimicking “cop voices” in order to raise money for police unions may call to mind moments from Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You (2018), especially the unforgettable mantra, “Stick to the script!”

However, the social justice ambitions of the film are tempered by inescapable moments of documentary satire. More than once in the series Sam and Pat give a direct shout out to Michael Moore, proclaiming, “This is what Michael Moore would do!” Indeed, the series mirrors Moore’s films in that the broader storyline seeks to culminate in a confrontation with an individual who wields great institutional power (such as Roger Smith in Roger & Me). There are two such confrontations, one with the president of the national Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) and the other with Senator Richard Blumenthal from Connecticut. Both meetings end with an anti-climactic whimper, but the former unravels in a manner that reads like a parody of a Michael Moore film. At one point, Sam and Pat attempt to confront the president of the Fraternal Order of Police, Patrick Yoes, at the group’s national convention. The filmmakers have already demonstrated that Yoes was one of the primary orchestrators of CDG’s malfeasance. Anticipation builds and Pat approaches Yoes with the query, “Hey, excuse me, Mr. Yates, right?” Yoes looks puzzled and responds that he doesn’t know a “Mr. Yates.” After initially concluding that it was another dodge, Pat eventually realizes that he got the name wrong and turns to Sam to express his regret: “Dude, I apologize, I fucked it up.” One of the series’ most pivotal moments is marred by a comic mishap that nevertheless centers the friendship of Sam and Pat. But of course, Pat’s initial reaction that the president was dodging him was not totally wrong. In spite of the misnomer, in all likelihood Yoes knew that Pat was looking for him and, even if the name had been correct, the result would probably have been the same. And, in a way, this is a more accurate indicator of systemic indifference and the need to tackle the problem in a more structural manner. Failure is likely more impactful and their ultimate success in getting Telemarketers on HBO manages to keep the campaign alive, even resulting in Senator Blumenthal’s recent announcement that he will heed Sam and Pat’s insistence on new legislation. An anti-climax short circuits our desire for an onscreen authentic reckoning, but at the same time reminds us of the deeper roots of exploitation.

“Jargons of Precarity”

Benedict Stork (Seattle University)

In each episode of the HBO Documentary series Telemarketers (2023), director and participant Sam Lipman-Stern references Michael Moore. This literal invocation of Moore compliments a stylistic and thematic echo as Lipman-Stern performs an amalgam of reflexivity, amateurish muckraking journalism, and documentary provocation reminiscent of Roger & Me (1989). Along with these spoken and formal signifiers, Telemarketers also shares that earlier film’s impulse to confront the powerful. Using what Paul Arthur dubs an “aesthetic of failure” (in a 1993 essay my title here plays on: “Jargons of Authenticity”), Roger & Me targets Roger Smith, the CEO of General Motors who helmed the company’s devastating abandonment of Flint, MI; the absent confrontation with Smith is replaced by Moore’s now signature performance of working class affect and identification with the laid-off workers. Telemarketers, on the other hand, begins as a madcap exposé of Lipman-Stern’s former employer Civic Development Group (CDG), pioneers of a particularly corrupt type of telephonic fundraising, before morphing into an investigation of the firm’s primary clientele, police unions. Here Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) lodges occupy the space of immunity that Roger Smith signifies in Roger & Me, representing an apparent shift from economic to state power and from a focus on unemployment toward corruption. However, I want to suggest, this apparent divergence is only an effect of the changed historical context, where unemployment in the 21st century is no longer a scandal but simply a feature of American life.

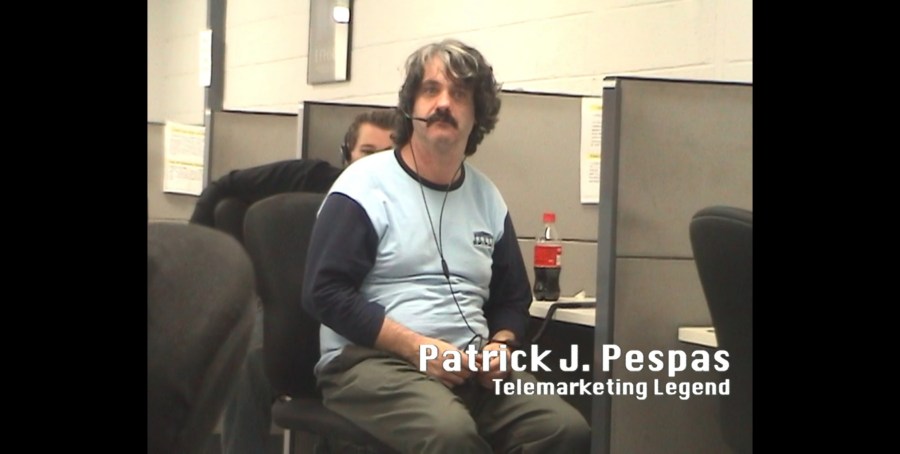

The most potent figure of Telemarketers’ implicit and symptomatic engagement with contemporary proletarian life is Lipman-Stern’s former co-worker, friend, and collaborator Patrick J. Pespas. With a striking resemblance to Michael Moore, Pespas is a sort of red thread running through Telemarketers, connecting Lipman-Stern’s experience working at CDG to the series’ off-and-on investigations of the industry and its clients.

Nicknamed by co-workers “Pat the Tapper, aka Pat the Smacker,” Pespas is immediately identified both as a “Telemarketing Legend” and drug addict. Though over the roughly 20 years the series covers Pat enters recovery, his addiction is a constant shadow faintly cast over the series’ penchant for displaying active drug use. Along with a certain charisma and Sam’s obvious affection for him, Patrick J. Pespas acts as a sympathetic, if at times laughable and embarrassing, member of what Marx called “the reserve army of the unemployed,” drawn in and out of the service sector to meet its contingent needs. Where Michael Moore’s schlubby outfit performs class identification, Pat embodies a sort of dexterous vulnerability, that, like his ability to spring awake from a dope nod to close a call, combines pathos with the hustler’s virtuosity. He is, in this sense, an apt avatar for the contemporary worker with nothing to sell but his labor power and nothing to lose but his (and his ailing wife’s) life. As the anonymous industry informant “Jeff,” tells Sam, “You want a good fuckin’ salesman? Hire a fuckin’ crackhead. […] I mean, think about it. Who’s gonna talk you outta money more than a dope head?”

This nexus of precarity and the machinations of contemporary capital that Pat represents is where Telemarketers comes closest to declaring its engagement with un- and underemployment. As one former telemarketer remarks, CDG “…provides a public service almost by accident. […] Providing jobs to people that are unemployable.” Like Pat, many of the former telemarketers Lipman-Stern interviews have criminal records, and what is presented as an irony by the series is in fact its (likely accidental) insight: the police unions the series eventually focuses on are a structural component in the production and management of the precarious labor force CDG and the rest of the service sector relies on. The more Sam and Pat pursue links between telemarketers and the police, the series dramatically gestures toward the threat of retributive violence from the police. Yet in their journey through a landscape of New Jersey strip malls, repurposed or abandoned warehouses, decaying infrastructure and underpass tent encampments, the danger of unemployment is far more palpable. Each scandal that leads to CDG temporarily shutting down and mutating is accompanied by job loss as former co-workers cycle in and out of call centers and other service industry positions.

In this way, the series only glancingly notes these general economic conditions underpinning the contemporary economy: a regime of accumulation based on the production, exploitation, and management of surplus population. This all comes to something of a head during a pivotal interview with former Federal Trade Commission (FTC) director David Vladek. Saturated with an underlying antagonism, the former regulator revels in having taken CDG on, jokingly suggesting, upon hearing CDG employed Sam and Pat, “Now I’m having regrets ‘cause we didn’t go after you guys as well.” Before the chuckles subside, Sam gently turns to police union involvement with CDG, opening a line of critical questioning about the limits of the FTC’s prosecution. Visibly uncomfortable, Vladek eventually concedes the police culpability in the scam. Here Pat becomes increasingly agitated, interrupting with:

Pat: But you didn’t go after the Fraternal Order of Police at all.

Vladek: Right

Pat: And then CDG people, who are making minimum wage, trying to pay their rent lost their jobs. That’s great.

Vladek: Yeah, well, I felt no sympathy at all for anyone who worked…

Pat: Oh, I’m sure you don’t.

Vladek brings things to a close, stating, “I did not care one whit that all of you guys were unemployed.”

If, per Arthur, Moore’s “aesthetic of failure” required a performance of working class “authenticity” to interrogate unemployment, Pat’s mere identity as a precarious worker, driven to telemarketing by the combined forces of addiction, criminalization, and wage dependency, requires no such pretense. Here, in the mess that is Telemarketers—and it is quite a messy mélange of performative documentary, exploitative class spectacle, and true crime serial—the combination of what Søren Mau, following Marx, calls the

“mute compulsion” of capitalist economic power and the repressive force of state power, cannot help but inscribe themselves in its images. As Pat says, following his exchange with Vladek, “I’m, like, nobody. I’m like Mr. Joe, 15-dollars-an-hour, ‘Hi, welcome to McDonald’s” type of guy. […] Who knows what we’re dealing with, you know? And they’ll—they’ll squash you like a bug.” Thus, while Roger & Me identifies and sets out to document and confront the ongoing process of late-stage deindustrialization by identifying an individual to hold to account, Telemarketers simply exists in the postindustrial wake where the figure of “Roger Smith” is dispersed into the impersonal “they.”