“Extracting Wine from a Grape: The Ferment of Found Footage Documentary”

Lisa Perrott (The University of Waikato)

Firing up fans and confounding critics, Moonage Daydream has been described as an “experimental cinematic odyssey” and a “colossal tidal wave of vibrant images and overpowering sound.” According to the Moonage Daydream official website – this film “is not a documentary,” but rather “a genre-defying cinematic experience.” But of course it also is a documentary and worthy of close examination precisely because of its ambiguous approach to the form.

Following the film’s release in September 2022, social media networks were ablaze with heated arguments. While some of the most ardent Bowie fans engaged in fierce debates about representation, there were also a range of conflicting views expressed about authorship, creative license, methodology, form, and the selection and salience of source materials.

A long-term ‘aca-fan’ of Bowie, I am also a scholar of documentary and audiovisual media. This positioning enables me to draw on my research into the fandom and participatory cultures associated with these topics, all of which informs my discussion of Moonage Daydream as an exemplar of the mutability of documentary film. By remediating the genre, this film pushes against expectations of biographical documentary, a finding that is supported by my survey of comments posted to social media by fans, along with published reviews by music and film critics.

Prior to embarking on directing Moonage Daydream, Brett Morgen had already instigated debate about documentary form and ethics. His biographical film Montage of Heck (2015) received criticism for the creative liberty taken in representing the late Kurt Cobain via animated sequences built upon archival audio and visual materials. In 2017, Morgen again challenged audience expectations with Jane by accompanying naturalistic footage (shot by Jane Goodall’s ex-husband) with an avant-garde score composed by Philip Glass. Extending his penchant for creating perplexing biographical films with found footage, Morgen’s next project became a petri-dish to experiment with alternative methods.

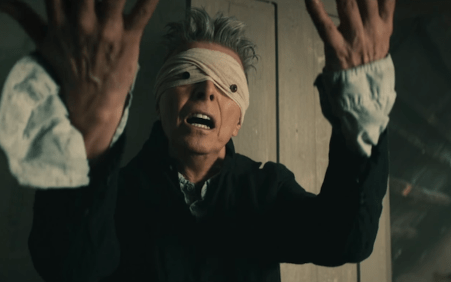

With official approval from Bowie’s estate and millions of archival pieces at his fingertips, Morgen began a seven-year journey of immersion, selection, and assemblage – a process he describes as intuitive and alchemical rather than intentional and methodical. Rejecting the conventions of expert analysis and talking heads associated with biographical documentaries, Morgen merged the indexical qualities of archival materials with surrealist poetics and music video aesthetics (see Fig 1). Although he crafted something new and dynamic, this intermedial convergence confounded some audience expectations and triggered a sense of discomfort, particularly for those anticipating the conventional evidentiary editing of facts or the linear structure associated with biographical documentary.

Taking inspiration from Bowie’s existential philosophies about transience and the value of embracing discomfort, Morgen put himself into situations that displaced him from his comfort zone. He approached Moonage Daydream in a way that mirrors Bowie’s creative process and replicates his treatment of music and video as time-travelling mediums.

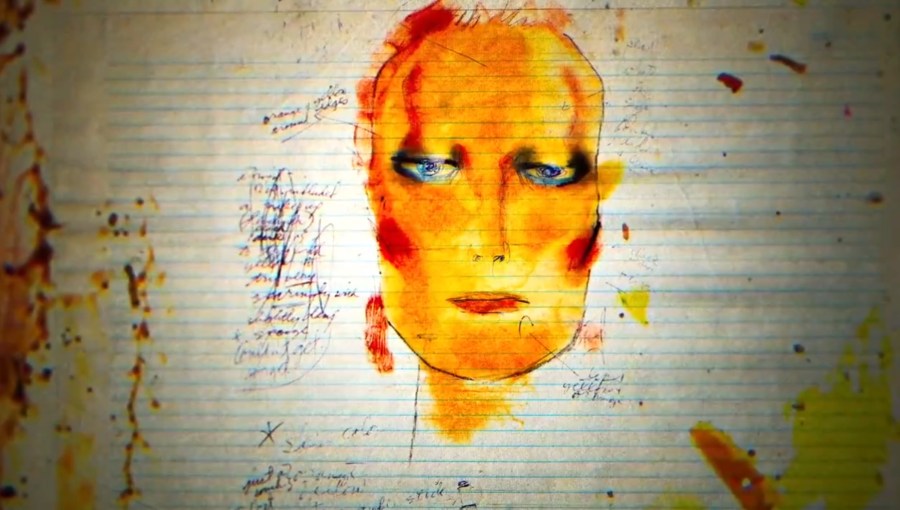

Experimenting with various methods used by Bowie, such as bricolage and the “cut-up method,” Morgen created an audiovisual tapestry, woven from disparate archival materials. Songs and vocal recordings are intertwined with photographs and film fragments from music videos, theatrical films, televised interviews, and live performance. These archival materials are remediated and enlivened by visual and sonic effects. Morgen even took the creative liberty of disassembling and reanimating Bowie’s hand-drawn sketches, paintings, and storyboards – much to the chagrin of some Bowie fans (see Fig 2).

While many fans responded to Moonage Daydream with great appreciation for Morgen’s portrait of Bowie as a transient figure with philosophical insight about existential serenity, there were also many who took issue with Morgen’s approach. One of the concerns raised was the sense that Morgen’s selection of materials was skewed toward particular phases and albums and therefore not adequately representative of Bowie’s oeuvre as a whole. Some fans complained that Bowie’s ‘best’ material (in their view) was excluded, while pieces of banal footage were (arguably) given too much screen time. This is a very subjective response by fans who may not have considered the unavoidable subjectivity of the filmmaker.

Related to these issues of representation and subjectivity, some fans asserted that Morgen wielded too much creative license by cutting up, reassembling, coloring, and animating some of the archival materials. While many reviewers were in awe of the reworked sonic arrangements, some expressed unease about the creative liberties taken by Morgen and by the team who rearranged the songs.

Some fans questioned whether Morgen had the appropriate knowledge, credentials, or depth of fandom to be directing an official biographical film about Bowie. Considering authorship from another perspective, Morgen has been criticized for failing to acknowledge the artists who collaborated with Bowie on his albums and music videos. This is a common oversight made by authors and directors who become immersed in the process of celebrating the work of a creative genius. While such a singular representation of authorship can appear idolatrous and ignorant of the realities of collaborative authorship, fair acknowledgement of Bowie’s many collaborators may have been difficult to build into a documentary intended to emulate the creative essence unique to Bowie.

While these issues of authorship, creative license, representation, and form provide fodder for ongoing debate, the question remains: what do we make of this uncertainty around Moonage Daydream’s status as a documentary? According to the Bowie fan whose IMDb review is titled “A Complete Turd”:

It was not even a documentary. It was just a bunch of old footage thrown together that had very little continuity and just jumped all over the place. They could have done a real documentary about his life and dove [sic] into his past and created a real story about his life and legacy.

Another reviewer bemoans “Moonage Daydream is billed as a documentary about David Bowie, but that’s stretching the term.” But, in contrast to these limited definitions of documentary, by stretching the imaginary boundaries drawn around perceptions of documentary, this film opens the way for new and fitting ways to assemble the audiovisual legacies of transformational artists such as Bowie.

Like Bowie (and documentary in general), Moonage Daydream is a mutable, transient text with chameleon-like qualities and the capacity to transcend conventions and norms. Provoking healthy debate, this film shows us that documentary filmmaking need not be constrained by convention. For Morgen, it was an intuitive process involving the fermentation of found footage. In his words, it was much like “extracting wine from a grape.”

“The Sun Machine is Coming Down (This Chaos is Killing Me)”

Sean Redmond (Deakin University)

To begin, I cut up some Bowie-esque lyrics and assemble them so:

You put lipstick on an elephant

And hung him dead upon a wall

while kitschy itchy Keaton’s sadness

frowned and drowned us all

As a fan, I found listening to David Bowie often brought together two contradictory modes of feeling: one where I felt like I was soaring through time and space – an awe-struck spaceman sailing on the starry shores of the cosmos – and one where I felt my body was being assaulted and penetrated by fragments of refracted chaos. This auditory, co-synesthetic schizophrenia involved expansion and contraction, communion and lonely despair, sun-drenched harmony and the pulling of shrapnel out of bone, skin, eye, and heart. Listening to Bowie’s vocalization and sci-fi lyrics enchanted and destroyed me in equal measure.

In Brett Morgen’s remarkable Moonage Daydream (2022), the colors and intensities of these propulsive and repulsive affective registers are carried through and along its shimmering, fragmentary imagery and pulsating editing (see Fig 1). The horizon of the documentary communicates as if it is a supernova that is slowly, chaotically dying, ready to be reborn again. This is no simple “rise, fall and rise metaphor” for David Bowie’s star image and artistic career, however, but rather the sensory essence of his various personae and a distillation of his philosophy that we age and die in a world that is inherently disorderly. As Bowie says in the documentary,

There is nothing to hold onto anything that is manifest seems farcical. There is nothing to hold onto – youth, physical things (pause), definitely possessions… the 20th century concern is how we put our new God back together again. I think we are coming into an era of chaos and chaos is meaning in our lives… chaos and fragmentation is something that I have always been comfortable with…

Moonage Daydream is composed of live concert footage, television and radio interviews, music videos, stills, “celestial” animation, and the artists that Bowie was attracted to or referenced in his music, such as Buster Keaton and Stanley Kubrick. As such, its formal or modal strategies are fairly conventional. We are gifted access to “backstage” or private Bowie and with this, the representation of authenticity or realness that accompanies such moments of introspection and self-revelation lays him bare. The documentary often captures Bowie alone in various Asian cities, as he walks through public spaces. The loneliness of the rock star is alluded to, while at the same time a type of mysterious Otherness enters these scenes through the way his “whiteness” stands out in these “Eastern” environments. Bowie speaks of isolation in the documentary and for the most part, he exists alone even when surrounded by adoring fans (see Fig 2).

To continue, I am riding the tram into work, scribbling down a stream of thoughts:

One eyed Jack snags a cat

Lonely on the 69th floor

Around comes ziggy smokin a ciggy

That dog is such a lonesome bore

Authenticity is of course a social construction, a representation that here seeks to mythologize Bowie. Moonage Daydream presents us with the myth of the genius artist. Bowie emerges as both a trailblazer, shaping trends in fashion and music, who opened up social identity to non-binary, liminal forms; and as a tortured soul painfully aware of the fame and consumption narratives that both gift him renown and the trauma of eternal visibility. Such superhero narratives are of course partial: they lead to omissions, such as the sexual assault, rape, and abuse allegations made against Bowie during his career.

A racial element bubbles beneath this star-in-tension: there is a whiteness to David Bowie which allows him to pass, to transgress, to consume the Other in those Asian cities he walks through. In one extended scene we follow Bowie through a series of doors and rooms until he sits quietly listening to “ethnic” music being played live just for him. In another, we see a shaman pull his fingers and hands and then spit a spray of (cleansing) water in his face – as if the exotic resides not just in Blonde Bowie but in this racial Other.

This scene is more complex, however. It appears in an extended montage sequence while the song Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide plays. Images of Bowie from the 1980s are intercut with a live stage performance from the 1970s (See Figure 3). His multi-million dollar Pepsi advert with Tina Turner is cut alongside footage of his mega concerts, Live Aid performance, Blue Jean music video, appearance as Jareth in Labyrinth (Henson, 1986), and as an aged John Blaylock in The Hunger (Scott, 1983). Near the end of this montage, we enter the ear of an animated, persona-changing Bowie as he begins to careen down a never-ending staircase. The impression here is that Bowie had been consumed by fame and a necessary career suicide had to take place to allow him to find his way again. Death haunts this montage but so does the sense that from that annihilation his artistic life began again.

To finish, I am walking alone at night in the city, with Lazarus playing on my headphones:

Your death came on like a song

Cratered me to sleep

Ain’t that just like you

I’m so low my heart hurts

But I know that you are free…

Moonage Daydream offers us a complex, sense-driven view of Bowie as a bi-focal star: as both a sun machine and an assemblage of chaos (See Fig 4). As a fan, the work moved (through) me, touched me, made me feel exalted and lonely – its gravitational pull both upwards and downwards, social and isolationist. Moonage Daydream is an affective documentary that moves beyond realism, verisimilitude, and factual observation. It embodies its mercurial subject matter and revels in the “frenzy of the visible” that Bowie represents. These sun-drenched and chaotic impressions linger on and on…