“Survival and Resilience”

Kyoung-Suk Sung (Max Planck Institute for Human Development)

Why is Korea consistently portrayed both domestically and internationally in close connection with the Korean War, even though the memory of the war pertains only to a specific generation? This question is crucial, particularly given that the younger generation experiencing the war indirectly, through books or films, often shows significant indifference toward the Korean War and the resulting division. In South Korea, the latent danger posed by North Korea is only recognized when concrete and visible events occur. Nonetheless, over the past few decades, numerous films have approached these themes by incorporating personal stories that demand significant empathy from audiences, such as Crossing (Tae-Kyun Kim, 2008), Dooman River (Lu Zhang, 2009), and Winter Butterfly (Kyu-Min Kim, 2011).

Hyun Kyung Kim’s 2023 documentary Defectors joins this tradition, focusing on the ongoing impact of the Korean War by highlighting the stories of North Korean defectors who made it to the South but then left South Korea to seek asylum or immigrate to third countries. Indeed, many defectors have found it difficult to settle in South Korea, leading them to voluntarily immigrate to third countries. Kim’s film provides a poignant portrayal of the harrowing experiences of North Korean defectors who continue to seek safe haven, connecting these broader stories to her personal family history, particularly to that of her parents, who are still haunted by the memory of the Korean War.

Defectors intertwines three personal stories: that of the director’s mother, who suffered in South Korea due to her father’s defection to the North; that of the director herself, who moved to the United States; and those of several North Korean defectors who have not yet found a place of belonging. Throughout, Kim’s calm narration guides the audience through these diverse ‘defector’ experiences. The film documents her mother’s life, marked by the hardships caused by her father’s defection (or disappearance), which left her struggling to sustain herself and her siblings in difficult circumstances. This narrative captures the remnants of the Korean War on a deeply personal level while situating it within a broader social context. Through the depiction of her mother’s longing for the education she was denied, illustrated through her worn notebooks and books, Kim shows the profound impact of historical upheavals on an individual life. The film candidly portrays her mother’s past and present, delving into the complex emotions she harbors towards her father, who was above the 38th parallel when the two Koreas were divided and whom she never heard of or from again. Additionally, Defectors introduces several North Korean defectors, who survived unimaginable hardships to reach and then leave South Korea. Their experiences, shared through interviews, reveal the trauma they carry, including the loss of family members and the constant fear of repatriation.

In a character-centric documentary, few cinematic elements are more powerful than the faces of the subjects themselves. Through close-up shots, Kim creates an intimate connection between the subjects and the audience, allowing viewers to witness the raw emotions on their faces. This is particularly evident in the sequences where the director’s parents and defectors discuss their thoughts on the divided Korea and their personal experiences. For example, the inclusion of the family photo of the director’s mother and various items she has collected from the streets emphasizes how history inflects personal, daily experience. Particularly impactful are the scenes where individuals sing. Music in this context can be seen as a gestural pattern, representing certain emotions in a way that is deeply intertwined with cultural and historical factors. Songs in films often connect with social events, capturing the attention of audiences across generations. Lyrics can serve as implicit commentary, revealing internal monologues of characters or offering insights from a narrative perspective. Additionally, songs act as markers of identity, reflecting people’s ties to their homeland. In Defectors, the sequences featuring the songs sung by the director’s mother and Mr. Kwon are particularly notable. The director’s mother, who grew up as the daughter of a defector, sings a poignant song mourning her lost daughter, embodying her unresolved emotional wounds and the pain of displacement. Similarly, Mr. Kwon sings while searching for a place to call home, expressing his ongoing quest for identity and belonging as a forced emigrant due to his country’s turbulent history. These songs illustrate their singers’ longing for lost family members and abandoned homelands. For Mr. Kwon, his Korean identity is reaffirmed through his performance, which triggers reflections on his past and present circumstances as a displaced person. Additionally, Mr. Kwon’s song serves as a surrogate message from the director’s grandfather, which her mother never received. This emotional connection between the songs highlights the film’s exploration of the unresolved emotional scars passed down through generations due to the Korean War.

Through these musical sequences, Kim effectively portrays the slow process of emotional recovery and reconciliation. The songs performed by Kim’s mother and Mr. Kwon are integral to the film’s exploration of identity, loss, and belonging. Kim’s mother’s song, mourning her lost daughter, reflects deep-seated sorrow and displacement, while Mr. Kwon’s song captures his ongoing search for home and identity. These musical moments bridge personal memories with broader themes, illustrating how past traumas continue to shape the present. By integrating these songs into the narrative, Kim enhances the film’s emotional depth and underscores the resilience of individuals as they confront their histories and navigate new lives.

“Things and Places Remembered”

Steve Choe (San Francisco State University)

As the number of Koreans who survived the Korean War (1950-1953) decreases with the passage of time, the role of media in archiving their memories for posterity increases in urgency and importance. During the three years of the brutal war, over four million military and civilian personnel from both Koreas were killed, left wounded, or went missing. Families were permanently separated following the division of the country in 1948 while mothers, fathers, daughters, sons, and siblings were arbitrarily stranded on opposite sides of the 38th parallel. Hyun Kyung Kim’s highly personal and affecting film Defectors (2023) traces the lives of those who continue to live with memories of loved ones and whose whereabouts remain unknown, even after seventy years. The filmmaker’s aging parents are central figures in the documentary. They suffer from invisible wounds deepened with memories of other painful losses: Kim’s sister Ae-kyung to Parkinson’s and Kim herself in her permanent departure from Korea. These departures then are overlaid with other instances of defection and other disappearances: namely Kim’s grandfather when he left for North Korea during the war; Mr. Kwon, a North Korean diplomat who defected while serving in Vietnam; North Korean women defectors who speak publicly at a conference in Washington, D.C.; and Kim’s father, who departs from the world at the end of the film. The interviews throughout Defectors attest to the filmmaker’s profound sympathy and affection for those who experienced permanent loss and whose melancholy forms the basis for seemingly impossible hopes in the future – of reuniting with family members, acquiring asylum status, or of national reunification. Kim’s camera records their anguished accounts and preserves them for the day when these hopes may finally be redeemed.

For the time being, Kim’s camera turns toward the worlds of these defectors as well as of those who continue to remember them. While Kwon speaks openly about his past experiences, he somewhat surprisingly seems unconcerned about the discovery of his general whereabouts. He recalls that he sold the foreign car that was provided to him, tax-free, to locals in Vietnam in order to help make ends meet. This illegal exchange, deemed by North Korean authorities to be capitalistic and individualistic, created problems for Kwon and compelled him to defect. His leaving cost his son and wife dearly. Remaining completely disconnected from them, Kwon’s forlorn face and weary voice, filled with guilt, express his unending sadness and perhaps profound regret for having made the decision to leave. For other defectors, Kim blurs their faces so as to respect their privacy and anonymity. Her camera turns away from identifying others who regularly associate with them, like Kwon’s South Korean wife, in case posterity will judge their public appearances politically compromising. In D.C., her gaze averts from faces and toward torsos and gesticulating hands as the defectors express their admiration for America through offscreen voice. We are hardly given a direct shot of the filmmaker’s own face, moreover, as she purposefully blocks it with her own camera.

Rather than dwelling on faces, Kim’s film almost obsessively shows the things used and the spaces occupied by the defectors: a clothesline behind a working-class home, a Korean floor table with medications and containers of food sitting next to plastic bags of ramyon noodles, folded laundry and a drawing of a young woman’s face, an ashtray full of cigarette butts in the corner of a garden. Each of these shots, forlorn like Kwon’s face, attest to objects that have been used to abide time and spaces that have not been fully lived in. They suggest the lonely lives of the defectors, who are only passing through, and who have resigned themselves to the practice of waiting. While Kwon passes time in his house in the U.K., he remembers and dreams of his home in North Korea.

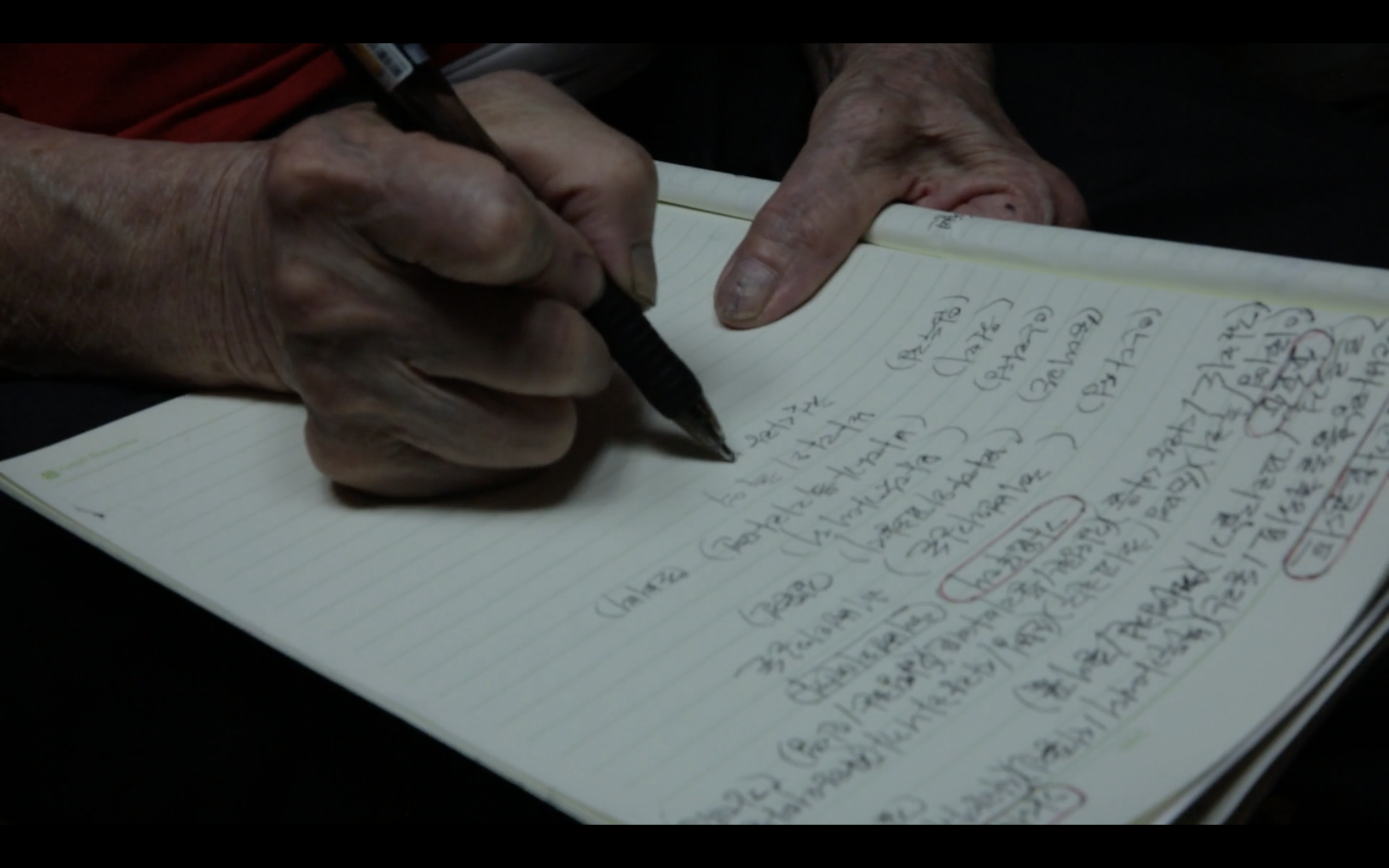

These shots of Kwon may be compared with those that comprise the worlds of the filmmaker’s parents. Kim’s mother is a hoarder. She surrounds herself with countless used and unused containers, unclaimed chairs, kitchen appliances, stuffed animals, wine bottles, throw pillows, stacks of plates – strewn throughout all the rooms of her apartment. The bathroom has become a storage room for more things while the flat surfaces in the kitchen are overloaded with countless coffee mugs and various bottles. In a heartbreaking moment, Kim’s mother says that she collects flowers in the room where the bedding for Ae-kyung has been left as it was, nestled among roses and poinsettias, because she is lonely. Her words confirm Kim’s guilt for leaving her parents alone. The filmmaker’s father, while not a hoarder, has kept a worn blanket she used as a child along with old towels dating from 1993. These are objects that clearly hold great sentimental value, but they also function as memorial objects for loved daughters who have passed or have been lost, who left and defected. They confirm that the past was once real, despite the world having changed too quickly, and that we can and must remember, despite the progressive inability to recall the past due to age. While watching television, Kim’s mother writes the names of singers and songs that appear in a notebook so that she does not forget. One surmises that the countless objects she has collected, many of them meant to be used and thrown away, are allowed permanent existence in this home, never to be forgotten and thus saved for posterity from a rapidly changing world outside that will not value them.

Various technologies featured throughout Defectors, like a cell phone, photographs, a digital camera, Google maps, even the notebook, draw attention to the important role that they play in archiving memories, particularly at the moment when the human facility for recall begins to fail. Kim’s film cuts between time and place: South Korea, D.C., the U.K., the U.S.A., New York, 2013, 2019, “eight years ago,” and “twenty years ago” (referring to footage from her film, What Are We Waiting For? [2005]). The fluidity by which Defectors moves between these times and places suggests that the boundaries between them are porous, that the past continues to resonate with the present. Archival military footage of the Korean War intertwines with shots of contemporary Korea. The way Kim’s mother turns her head in the present is juxtaposed with a shot of her turning her head in the same way twenty years ago. With Kim’s voiceover, the film moves through these times and places in the manner of an essay film, invoking her own activity of recording, archiving, and remembering. When Kwon’s wife makes cucumber kimchi in the U.K., mixing the spiced chives with her hands, they remark that the smell makes them both salivate. “I guess it’s because we are Korean,” Kim says. Here it is her ethnicity that provokes an involuntary corporeal response.

Indeed, the film attests to the capacity of the body to never forget. Kim grew up in a house where, as she mentions, the smell of the Korean War was “suffocating.” Recording technologies do not function in this manner. Instead, they function as prosthetic extensions of our own capacity to recall the past. Aging, the fear of loss, and the deterioration of the body, Defectors seems to suggest, compel a desire to be surrounded by meaningful things and media so that we will never forget. Moreover, as recording technologies attest to the presence of lost loved ones, they also confirm a “country they never knew and a people they never met,” to cite a plaque in the Korean War Memorial. For many of us who did not experience the war and its losses directly, Kim’s film solicits viewers to grieve and sympathize with those that defected. It memorializes individuals who are remembered by those interviewed in the film, for Kim’s sister and grandfather and for countless other defectors who will remain anonymous so that we may share in their, as Kim puts it, “community of sadness.”