“Shooting from the Mussy”

Jennifer Moorman (Fordham University)

As its logline asserts, “Body Parts traces the evolution of ‘sex’ on-screen, from a woman’s perspective.” The project was conceived as an exploration of the use of body doubles, but somewhat serendipitously a few months after production had begun, the MeToo movement rose to prominence and the filmmakers widened their scope to encompass many facets of sexual intimacy and consent in Hollywood. The film anticipates developments in industry practice and, in a sense, documents them in real time as they happened. The filmmakers had already shot interviews and reenactments of scenes with intimacy coordinators, at least a year before the use of intimacy coordinators would become (increasingly) widespread practice in Hollywood. By the time of the film’s release, the conversation that Body Parts initiates could not have been more relevant.

In so doing, the film employs a fairly conventional framework of talking heads intercut with montages of Hollywood film clips and occasional reenactments of Hollywood film shoots. It is notable, however, for its wide variety of interview subjects – along with actors, directors, producers, and academics, we hear from intimacy coordinators, entertainment lawyers, body doubles, and visual effects technicians. In terms of information, the film likewise aims for breadth rather than depth; it touches more or less briefly upon many topics, including sexual misconduct in Hollywood and the exposés of it that emerged from the MeToo movement, to the Production Code, to the prevalence of body doubles and digital retouching, the rise of intimacy coordinators, and some of the ways that women filmmakers and TV producers have begun to explore images of women’s sexuality with more depth and nuance.

Despite all of the ground that the documentary covers, it obscures key information. None of the clips are attributed, and they are rapidly edited together. Some are iconic, others are lesser known but recognizable, but most would remain a mystery to me. Similarly, the voiceovers are often unattributed, leaving us to guess at who is speaking when they’re not visually depicted. At times the images’ meaning and/or their connections to the words being spoken by interview subjects, likewise remain ambiguous. For instance, as someone (Mick LaSalle?) explains in voiceover that, “in American movies there has always been limits to who’s allowed to be sexual,” we see an image of a nude Kathy Bates stepping into a hot tub. Does this image of a fat woman – one of the groups who are described as not being allowed to be sexual – gently contradict or provide a counterexample to the voiceover’s statement, or are we supposed to extrapolate that this scene is supposed to be humorous rather than sexy?

After speaking with the film’s director, Kristy Guevara-Flanagan, and producer Helen Hood Scheer, I came to understand that this ambiguity was a way to avoid being “too pedantic.” A thesis of sorts emerges by the end: women have been harmed by cinematic representations and production practices alike throughout Hollywood history, but women’s sexuality should be celebrated rather than censored and this can only happen with more women in positions of power. However, the filmmakers want viewers to draw their own conclusions as well. Rather than a coherent argument, then, we are offered a series of impressions. From that perspective, the unattributed voiceovers, by separating the statement from the speaker and their profession, gently challenge the claims to authority that are typically vital to the expository mode. Similarly, we are called to accept the images not as particular examples of cinematic representations so much as emblematic of certain types of representation. Some of the clips are clearly illustrative of a point being made on the soundtrack; others are, as Guevara-Flanagan puts it, more “playful or cheeky” in evoking a mood or general tendency.

Guevara-Flanagan explains that she wanted to incorporate a near-comprehensive range of examples from US film history, diverse in terms of genre, time period, and performers’ identities. Indeed, the more than 800 clips form a dizzying array. The film encompasses US popular television as well as Hollywood cinema. But for me, one industry remained an absent presence throughout: adult film. In a project designed to trace “the evolution of ‘sex’ on-screen,” with one of the world’s foremost porn scholars (Linda Williams) as our guide, it is a glaring omission. Although it is often framed by laypeople as uniformly exploitative and misogynistic, the adult film industry arguably has often been ahead of the curve when it comes to issues of consent. As Constance Penley suggests, even prior to MeToo, there had been “a more developed everyday conversation about consent that goes on in the [porn] industry than you can find anywhere else.” And with regard to one of the primary correctives proffered by Body Parts – more women filmmakers – I found that, at least before MeToo had risen to prominence, women had many more opportunities to direct major productions in porn than in Hollywood.

But whether in Hollywood, popular television, or porn, it is clear that exploitation, distortions, and omissions overwhelmingly persist in cinematic depictions of women’s sexuality. In the end, Body Parts provides a useful jumping off point for thinking about the politics of consent and some of the ways that sexual representation has been shaped by regulation, production practices, and cultural shifts over time. In the process, productive contradictions emerge. Joey Soloway, for instance, explains that all of their work has been “an attempt to investigate the male gaze, all these ways in which the camera has kind of stood in for an assumed masculine protagonist, and to kind of reset it, saying ‘I’m the subject; you’re the object.’” And although the film overall suggests that having more diversity behind the camera will lead to more diverse representations onscreen, cis male cinematographer Jim Frohna says that Soloway, as showrunner for Transparent, would tell him to shoot from his “mussy,” and he concludes: “I don’t think that men only have a male gaze and a woman would only have a female gaze.” (Interestingly, “mussy” is not defined in the film. Frohna and Soloway seem to be employing it to mean “male pussy” – equivalent to the queer slang term “bussy” – but Bowen Yang coined the term to signify “mouth pussy.”)

As much as I would have liked to see ideas like that fleshed out (as it were), I appreciate the film’s refusal to dismiss sex scenes as “gratuitous.” Whereas a documentary about MeToo and the many misrepresentations of women’s sexuality in popular film and TV could easily have lapsed into sex negativity, Body Parts instead emphasizes that, as actress Emily Meade puts it, “nudity and sex are a really beautiful way to show things without telling them and […] a vital part of storytelling.”

“Ethical Body/Unethical Parts”

Eleni Palis (University of Tennessee)

At first glance, Body Parts (Kristy Guevara-Flanagan, 2022) seems the epitome of a #MeToo or #TimesUp film, a product of recent Hollywood reckoning regarding the treatment – on and off-screen – of women, non-binary, and trans people. However, while Body Parts does incisively critique Hollywood sexism, ableism, and systemic exploitation (and demonstrate ameliorating efforts, including intimacy coaches), the film’s formal structure and style addresses foundational film theoretical questions about historiography, archive, and the ethics of rewatching.

The title image for Body Parts (Kristy Guevara-Flanagan, 2022) introduces an anachronistic sense of film materiality. The digital image shudders as though projected on a damaged film strip marked by dust, grain, and decomposition, while a film projector whirs on the soundtrack. Often, the addition of aesthetic film-material markers in digital projection signals generalized nostalgia or pastness, but here it introduces a deliberate meditation on Hollywood history and ethical handling of archival film material. Much of Body Parts’ examination of sex and sexuality onscreen combines reenactments of Hollywood production practices, talking-head interviews with Hollywood luminaries from Jane Fonda to Guinevere Turner to Alexandra Billings, and an impressive variety of clips from Hollywood film history. These clips, what I have elsewhere called “film quotations,” function like the literary pull-quote or quotation in their enunciative power: as support, counterpoint, or visual evidence. In amassing quotations of dizzying quantity and variety, Body Parts proves its historiographic rigor, mining a wide range of American film-cultural production for what it can tell us about the presentation and representation of female, femme-presenting, and queer bodies. The assembled archive also doubles as an indictment of Hollywood. For instance, the many film quotations that make up a montage of predatory audition scenes or that catalogue the white cis-male screenwriter’s self-involved struggle reveal Hollywood’s overwhelmingly white, straight, Eurocentric, heteronormative, and male-dominated perspective. This archive also reveals the relative paucity of images detailing consensual, joyful female, queer, and trans images of sex and sexuality on film. Body Parts’ archive reveals what narratives are privileged in film history and where glaring absences remain.

The film’s most evocative moments emerge when Body Parts struggles against its own archive. A traditional expository documentary structure demands that if talking-head interviews discuss a specific sex or nude scene, the film should subsequently cut to the scene in question, using evidentiary editing so that the film quotation illustrates or supports the interview testimony. Yet, Body Parts’ interviewees often detail confusion, coercion, or consistent disregard for boundaries or safety on set during sex and nude scenes. And here emerges Body Parts’ central ethical dilemma: how can we re-view, assess, critique, cite, or indeed, teach film history without perpetuating the initial violence of their creation? How do we reckon with the film-historical record without replicating the exploitation in its production?

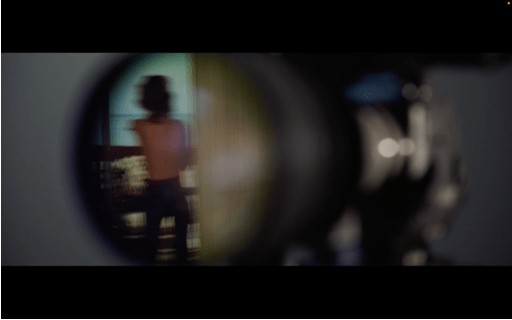

Body Parts works to mitigate the representational violence in reappropriated images by repeatedly and literally turning to the filmic apparatus. For example, when Rosanna Arquette recounts her experience on the set of S.O.B. (Blake Edwards, 1981), describing how she was instructed moments before shooting to perform topless, rather than wear a previously-agreed-to bikini, the film includes the S.O.B. scene in question, but holds the coerced moment at a distance. As in more traditional documentary form, Body Parts cuts to the shot of Arquette disrobing, but Guevara-Flanagan’s film alters the quoted scene by fragmenting it, shooting it reflected in a camera lens. The distancing effect approximates what Jaimie Baron calls an “occluded gaze,” obscuring all but the outlines of Arquette’s body. This occlusion mitigates the ethical ambiguity of this moment, simultaneously revealing and refusing the voyeuristic desire with which spectators might approach this moment. Instead of leering at Arquette, Body Parts reenacts the scene’s moment of creation and refocuses onto the shooting camera, prompting us to imagine the men behind the lens, physically and metaphorically. By extension, this image indicts the industry and the ideology that shielded and supported this predatory gaze.

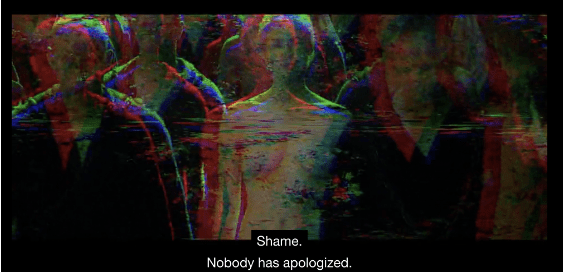

Body Parts’ structure—part history, part critique, part recommendation for the future—repeatedly struggles against its constitutive parts, its evidence, its archive. Guevara-Flanagan registers the ambivalence in reappropriating unethically produced images, the parts that populate Body Parts, by expanding the visual techniques that may occlude the viewer’s gaze onto unethically-produced images. For example, during a quotation from the Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-2019) “naked walk of shame,” anachronistic VHS-style color distortion obscures the nude body double. The disjunctive combination between a video playback glitch and a contemporary subscription television show sidesteps a commentary on technological stability or decomposition (as might arise from this effect on video-native media) and instead, presents a layered, multiple image. The color-separated repetition, superimposing the image on itself, mitigates the stark nudity and offers a visual metaphor for the multiplicity of gazes to which this image is subjected, as if visualizing how Body Parts overlays a more ethical, re-evaluating gaze upon the original, objectifying perspective of its TV origins.By foregrounding the cinematic apparatus while re-viewing coerced, non-consensual, or ethically ambiguous moments from film and television history, Body Parts broadens its political aim beyond the “usual suspects” of #MeToo. In what seems a pointedly deliberate delay, the film forestalls any mention of Harvey Weinstein for over an hour, and he is finally introduced by the line “Harvey Weinstein is not the only one.” This structure registers and resists Weinstein’s gravitational pull in popular media, how he threatens to stand in as singular “Hollywood predator” synecdoche and thereby overshadow the broader industrial problem that #MeToo, as viral hashtag, initially revealed. The film is less persuasive when considering the accusations or litigation surrounding particular predatory Hollywood figures, including Kip Pardue and James Franco. These specific examples lean toward triumphalist narrative arcs, suggesting that one successful lawsuit might change the system. As the many film quotations and interview testimonies suggest, this issue is not singular but pervasive.

Body Parts’ visualizes the formal, technological, and industrial challenges that American shared visual culture and history presents. In leveraging strategies of occlusion drawn from across film history—from the opening titles’ film-strip grain and decomposition to the Game of Thrones’ analog video glitch—Body Parts visualizes two intertwined ideological and industrial problems—the history of exploitative production practices and the ethical dilemmas inherent in reusing exploitative materials. As Body Parts makes clear, these problems span film history and technology, seemingly constitutive of the apparatus of American image-making. These incisive provocations counter a view of this film as a solely #MeToo film; they cut to the heart of contemporary archival debates, of ethical ambivalences in viewing, and new possibilities for film historiographical futures.