Documenting Politics in the Age of Trump

Maria Pramaggiore (Maynooth University)

On 12 January 2017, the UK Daily Mail reported on disgraced US politician Anthony Weiner’s hope for reconciliation with his estranged wife, Huma Abedin, after his stint at the Recovery Ranch in Tennessee to deal with his apparent sex(ting) addiction. A British tabloid’s interest in this saga suggests that Weiner’s stated reason for cooperating with his former aide Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg on the making of Weiner—that posterity might view him as “more than a punch line”—remains an unrealized ambition. Weiner’s durability as late night comedy fodder was confirmed a month after the Daily Mail piece, when a major snowstorm shut down the Northeast and The Late Show’s Stephen Colbert quipped: “Here in New York City, we got 10 inches. And for once, it wasn’t a text from Anthony Weiner.”

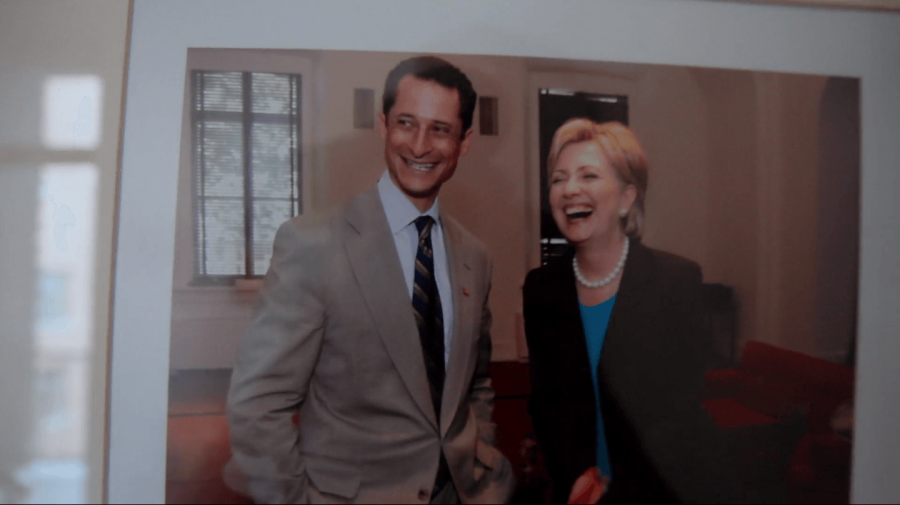

A film that Christopher Orr rightly calls “arguably the best documentary about American politics in many years” (The Atlantic), Weiner opens by quoting Marshall McLuhan to help explain the epic scandal that brought down seven time Congressman and aspiring Mayoral candidate Weiner twice, in 2011 and 2013, and quite literally cock blocked Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential bid. “The name of a man is a numbing blow from which he never recovers,” the title card reads, proposing that Weiner was saddled with a name that turned him into a penis-obsessed sexter and serial cybercheat.

But, thankfully, the film refuses to rest on any simple explanation for the events it observes. Using a combination of observational strategies and formal interviews, Weiner is a riveting documentary whose power derives as much from the filmmakers’ intimate access to Weiner and Abedin as it does from Weiner’s cringe-inducing recklessness. Intended as a redemption tale—F. Scott Fitzgerald’s elusive second act—the film instead documents the second round of a sordid affair that would continue to unfold well into 2016, after the film’s release. Timing proves important in matters personal and political: when the timeline of events becomes a problem because Weiner apparently sexted several women after his public mea culpa, he rehearses a defense popularized by another New York City icon, the TV series Friends. He implies, in not so many words, that he and Abedin were on a break.

Weiner and Abedin are compelling, photogenic subjects: he is dynamic, narcissistic, and unpredictable whereas she is mature, measured and composed, possibly drawing upon skills learned from her mentor Hilary Clinton. Despite the deeply personal nature of the story, the film’s most poignant moments are not the ones that feature an initially supportive and then increasingly anxious and withdrawn Abedin, fascinating as it is to watch her struggle to maintain her dignity and balance her marital embarrassment with her professional commitments to Clinton.

The truly heartbreaking scenes are those that explicitly dramatize the crisis in political leadership that enabled the 2016 election of Donald Trump. Throughout Weiner, ordinary New Yorkers struggle in vain to make sound political choices, weighing Weiner’s untrustworthiness against his likability and progressive positions. At a public event at City Island and at Gay Pride, working class people, people of color, and queers voice their support for this flawed fighter who they seem to think is worthy of their sympathy and a second chance. Desperate to change the narrative, one woman shouts: “we’re from the Bronx, we don’t care about that personal stuff.” But most New York voters, it turns out, did care, and Weiner came in dead last in the primary in a field of five.

The film might usefully be considered part of a trilogy, along with Primary (Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, Albert Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker, 1960) and The War Room (Chris Hegedus, D.A. Pennebaker, 1993). As a series, they document the long history of the media’s growing influence in American politics and point to the sanctioning of performative and narcissistic modes of ‘alpha’ masculinity that led to the election of a reality TV president.

The Laws of Entertainment Gravity

Jason Middleton (University of Rochester)

Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg’s Weiner (2016) follows the example of notable documentaries like Primary (Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, Albert Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker, 1960) and The War Room (Chris Hegedus, D.A. Pennebaker, 1993) in using the ready-made arc of a political campaign for its narrative structure. A comparison among these documentaries from three distinct historical moments bears out Rick Prelinger’s claim that mainstream documentary in the United States has increasingly turned toward conventional narrative arcs, character psychology, and the depiction of individual struggle and inter-personal conflict. Where The War Room focuses on how the larger political machinery manages a candidate’s sex scandal, Weiner demonstrates little concern for the politics of the NYC mayoral campaign, instead using a candidate’s sex scandal to focalize its portrait of a public figure’s personal pathology and the dissolution of his marriage.

Where The War Room draws viewers into a story that fits Prelinger’s description of “insurmountable problems…frequently solved,” the abject failure of Anthony Weiner’s campaign will be familiar to any viewer from the get-go. Even the ever-proliferating portrait documentaries of flawed and self-defeating social actors like American Movie (Chris Smith and Sarah Price, 1999) follow their protagonists toward some form of success and redemption in the end. Without the prospect of any such happy ending for Anthony Weiner, Kriegman and Steinberg’s narrative structure invokes the feel-good underdog story arc only to demonstrate the impossibility of its realization. Weiner’s narrative instead takes a form closer to a film like Double Indemnity: Weiner opens with a confessional monologue from the end of its story, once the election and his political career are lost. We then flash back to recount the events that led inexorably to this outcome.

Weiner makes liberal use of the voluminous archive of television news clips about Weiner and his scandal and frequently documents the politician’s frustration with the press’s obsession with his sexting scandals in lieu of the political issues central to his campaign. But the film itself develops no perspective on these issues either; an uninformed viewer would gain little insight to the political stakes of the election and the significance for the city of de Blasio’s subsequent victory at this historical juncture. Purporting to critically analyze a media-fueled scandal, the film instead redoubles the spectacle through its singular focus on Weiner’s character flaws and the imbricated unravellings of his campaign and his marriage. The film leaves little open to interpretation, aggressively shaping the intended meaning of its footage through montage and stylistics of cinematography.

One sequence, for example, cuts between temporally disparate shots of Weiner and Huma Abedin performing domestic routines with their toddler and news coverage of the couple’s public statements on the sexting revelations. The couples’ interactions at home are innocuous and register no particular conflict between the two. But through montage, media commentary on the “spousal abuse” the press infers from the couple’s “Good Wife” press conference serves as soundtrack to shots in which, for example, Abedin picks up her son and leaves the room while not looking in Weiner’s direction. Reinforced by a series of voyeuristic framings through doorways, the film invites us to read such shots as signs of Abedin’s alienation and the disintegration of their relationship.

Similarly, hopeful scenes are constructed through montage as well—the film assembles highlights of Weiner at his best, displaying his boyish energy as he works the crowds at street parades. But these scenes, always set to upbeat music, function ironically. They invoke a differential in perception between Weiner at the time of filming and the viewer’s awareness of how short-lived his hopes for success will prove. The film’s structure frames Weiner in these scenes as a Bergsonian comic figure—the viewer is offered a superior position from which to judge the manifold forms of denial that fuel his optimism. And this viewing position is not unlike the one constructed by the cable news pundits and late-show hosts for whom Weiner serves as perfect comic fodder.

Weiner’s most insightful (and perhaps likeable) moment comes toward the film’s end, when we return for the final time to the interview used to open the film. In this clip, he comments upon the documentary Weiner itself. The sexting scandal, he says, has rendered meaningless anything else he says or does: “[t]he laws of entertainment gravity are going to suck the documentary into the same vortex.” You may think you want to tell a different story, he says to the filmmakers, but the film cannot be received otherwise. Indeed, as the film draws to a close and we watch Weiner and his young son surrounded by reporters after voting for himself in a final, futile gesture, his son begins to cry as the cameras snap away. Weiner could invite its viewer to look critically upon the news media’s glee in how the image of this failed photo op will signify—as crystallizing Weiner’s simultaneous professional and domestic implosions. But the moment is consistent with the film’s storytelling imperatives: it offers the viewer little difference in perspective from the reporters and pulls us toward an uncritical complicity in the moralizing narrativization of the image.

As you both mention Primary, one of the more telling moments of the film is when Weiner starts losing patience with the filmmakers’ questioning and says something like, “I never thought I’d get so many questions from a fly on the wall.” (I’m obviously paraphrasing. The actual line was even better.)

LikeLike