“Doped-Up Authorship”

Travis Vogan (University of Iowa)

This last December, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) banned Russia’s entire national team from the 2018 Winter Olympic Games in South Korea because of an intricate state-run doping program. The unprecedented punishment—levied for an unprecedented offense—forbade Russian officials from attending the event and removed the nation’s flag from its Opening Ceremonies. It is difficult, of course, to divorce the IOC judgment—which Russia has chalked up to a politicized conspiracy that contradicts the Olympics’ apolitical pretensions—from the country’s alleged meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. While Russia cuts a particularly suspicious figure in contemporary global politics, the nation’s athletic programs have long been suspected of fostering performance enhancing drugs, and, just as important, developing inventive ways of evading detection.

Released by Netflix in August 2017, Bryan Fogel’s Icarus offers some useful context for understanding this controversy and the history of doping in sport. The documentary begins as a first-person exposé on the ease with which well-resourced athletes can use performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) without being caught. But the film quickly transforms into a far more compelling investigation of Russia’s intricate doping practices. Icarus provides a glimpse into the cloak and dagger efforts Russia allegedly took to secure an edge in international competition. Beyond the tale it weaves, Icarus illustrates some of the aesthetic and ethical pitfalls that mark first-person documentaries in which filmmakers’ aggressive cultivation of their personal brands butts up against their subject matter and sources.

Icarus opens with a montage of photos and audio clips of since-exposed athletes denying the use of PEDs along with George Orwell’s oft-quoted passage: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act.” The unambiguous sequence heavy-handedly suggests sport has become such a realm of “universal deceit” that they could use some truth-tellers. Fogel, a serious amateur cyclist who idolized Lance Armstrong and was devastated to learn of his transgressions, nominates himself to get the ball rolling. He set out to prove the systems in place to test athletes were “bullshit” by competing in France’s Haute Route—the world’s most strenuous amateur cycling competition—with the aid of PEDs and without being caught. Fogel presents his gambit along the lines of Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me (2004), and the film follows him as he trains, dopes, and competes. The filmmaker’s approach, however, swaps Spurlock’s affable rube persona for that of a mostly grating bro who continually emphasizes how “insane” his project is while wincing in pain for the camera as he shoots drugs into his ass.

Fogel recruited a series of advisors to help create a doping program and avoid testing positive, a group that includes Don Catlin, the former director of UCLA’s Olympic Analytical Laboratory. When Catlin gets cold feed—understandably concerned about how participating in such a stunt might harm his professional credibility—he connects Fogel with Grigory Rodchenkov. Like Fogel, Rodchenkov was once a serious amateur athlete who didn’t quite have the stuff to go professional—even with the help of PEDs. He became a chemist and eventually ran Russia’s anti-doping lab. Depicted as a quirky mad scientist, Rodchenkov agrees to help Fogel without reservation. In fact, the anti-doping expert seems to have a passion and flair for getting around drug tests. “I am mafia. This is mafia,” he drolly says while arranging tubes of Fogel’s urine in preparation for the Haute Route tests. Their experiment, however, ends on a disappointing note when Fogel’s doped-up performance produces worse results than when he competed clean the previous year.

It seems the story might end at that point—Fogel proved he could get around drug tests, made a cool Russian friend, and discovered that no amount of drugs could transform him into a professional-grade athlete. But soon thereafter, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) charged Rodchenkov’s lab with orchestrating a doping program—allegations that forced Rodchenkov to resign and fear for his life. At this point, Icarus pivots away from Fogel’s experiment and becomes an investigation into the system Rodchenkov oversaw. The filmmaker aids Rodchenkov’s passage into the United States and stows him away in an undisclosed location. Rodchenkov has good reason to be worried. Shortly after his resignation, his colleague and friend Nikita Kamayev died of a mysterious heart attack at 52—a death many suspected was an assassination.

Icarus makes no disclosure of Fogel and Rodchenkov’s agreement (assuming they made one), but it seems likely Fogel explicitly or implicitly made arrangements to help Rodchenkov hide in exchange for his continued cooperation in the film. The filmmaker brokers Rodchenkov’s transformation into a whistleblower who details the sophisticated doping program he led that helped Russia to dominate the 2014 Winter Olympic Games it hosted in Sochi. Rodchenkov links the program all the way to Russian Sports Minister Vitaly Mutkov—who has since been elevated to Deputy Prime Minister—and Vladimir Putin.

Fogel certainly stumbled onto a great story. But the filmmaker dulls its impact by insisting that he remain front and center. Why, for instance, did he persist in including the portion about his mostly failed and ultimately rather mundane doping experiment as the film’s first act when Rodchenkov’s story is so much more compelling, important, and textured? The introductory portion and narrative pivot, I suppose, may heighten the film’s dramatic pull. I, however, am far more interested in the story of what might be the greatest ever Olympic conspiracy than an amateur cyclist who decides to try PEDs to prove an obvious point about ineffectual drug testing protocols—one that is reinforced every time we learn of yet another athlete who has spent years doping.

While Rodchenkov and his story are gripping, Fogel’s role and presence seem both forced and ethically suspect. The documentarian, for instance, served as an intermediary between Rodchenkov and lawyers when the scientist was subpoenaed by the Department of Justice to discuss his role in the doping conspiracy. Fogel simultaneously helped Rodchenkov tell his story to the New York Times, which used it to publish a May 2016 story on the conspiracy—a report that is, incidentally, far more informative than Icarus. The Department of Justice, however, was not privy to Rodchenkov’s collaboration with the Times. As a result, the miffed agency walked back on the arrangement it promised the scientist in exchange for his cooperation. Icarus does not detail precisely what agreement the DOJ annulled, but it seems only to have potentially increased Rodchenkov’s vulnerability. The Times report mentions Fogel’s role in organizing its conversations with Rodchenkov and his documentary project, providing some advance publicity for both. The article is far from sponsored content, but Fogel and his project certainly benefitted from ensuring Rodchenkov talked to the Times. It is unclear what Rodchenkov gained outside of perhaps discouraging assassination attempts by broadcasting his fears for his life.

Icarus does, however, make some interesting points. It outlines, for instance, how Russia’s drug-fueled success in the 2014 Winter Olympics spiked Putin’s previously sagging approval ratings. This sudden surge in popularity, Rodchenkov suggests, emboldened Putin to invade Ukraine shortly after the Olympics. Rodchenkov never expresses much in the way of remorse for masterminding the doping program. In fact, he seems proud of the clever strategies he pioneered. But he does lament the political and military efforts he indirectly aided. The Russian government has unsurprisingly denied the existence of a state-run doping program and dismissed Rodchenkov as an unstable lone wolf. Putin condemned his claims as “the slander of a turncoat.” The fact that Mutkov has since been promoted from Minister of Sport to Deputy Prime Minister of the entire nation suggests that Russia, if anything, has doubled down on its denials.

Icarus’s interesting moments, though, are often undercut by Fogel’s continued insistence on inserting himself into a story to which he does not always seem relevant or even particularly helpful. I was left wondering what this film ultimately seeks to achieve. It is obvious Fogel has seen a bunch of mainstream documentaries; it is also clear that he hasn’t made any. Icarus demonstrates much of the hubris its title references.

“Some Kind of Monster”

Robert Cavanagh (Emerson College)

Icarus, Brian Fogel’s tabloid exposé-turned-spy-film about doping in sport, opens with a title card: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act. George Orwell.” It is doubtful that Orwell ever actually wrote or said this, though the phrase is popularly attributed to him.

This confusion about authorship is appropriate for a film with Icarus’s unusual history. Icarus is so disjointed that I hesitate to call it a unified film: Fogel and an enormous team of producers (the credits list 31 of various sorts—executive, associate, and archival—divided into a score of teams) and editors assembled and reassembled the film from the evidence of two conspiracies. In the process, the producers remix contemporary documentary aesthetics at a dizzying pace: Morgan Spurlock-style gonzo documentary, Brett Morgen-esque montage, animated explainer video, and quirky character study à la King of Kong (Seth Gordon, 2007) or the early work of Errol Morris. The result is a vulgar aesthetic built from the popularization of digital videography and based on expediency.

If you want to insist upon a narrower, more embodied construction of cinematic authorship, you can probably divide the film’s creators into three separate categories: Fogel, his co-conspirator Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, and the aforementioned lab technicians who slaved in post to give the film enough life for Sundance. But I see Icarus as the Swamp Thing, vomited up from the ooze of corruption, chemicals, and media that constitute contemporary sports. The finished product is an inevitable accident at the intersection of a documentary industry that has discovered how profitable sports can be and a mediascape that encourages everyone to be a filmmaker. This should not diminish its achievement: go ahead and give Fogel an Oscar. Icarus is exactly what you’d hope to get from an expanded field of sports coverage: an intimate look inside the world of sports that traditional perspectives have kept invisible. Fogel’s camera captures images you won’t see anywhere else: the athlete shooting viscous testosterone into his ass; close-ups of the enraged and disappointed World Anti-Doping Authority (WADA) authorities as they are confronted with evidence of their own ineptitude and complicity; a man saying goodbye to his wife before he goes into hiding, leaving her and his children to answer to Putin for his actions.

Like so many monsters, Icarus is the product of a mad scientist. What ties the film together is Rodchenkov’s recognition that he and Fogel had the same agenda: to use documentary to confess and create scandal. Icarus is highly reflexive: both men looked on the documentary act as an essential step on the way to a more important scene of revelation. But the finished film is an improvisation. Fogel’s plan to demolish what is left of professional cycling’s credibility was half-baked: he had no idea how to get his urine tested by WADA and the drugs failed to improve his performance in the Haute Route. Consequently, after the race, Fogel was not only physically and mentally exhausted but devastated by the collapse of the film he had been making up to that point. It was then that Rodchenkov took over production and it is at that moment in the film—a little over a third of the way through—that Icarus shifts from a reconstruction of an athlete’s doping procedure to Rodchenkov’s audition for a reality tv show confession and exposure of the Russian doping scheme.

The final third of Icarus reflects on the power of international sport as propaganda, a power that every nation state that has ever participated in the Olympics has tried to exercise. In what is probably the film’s most coherent and cinematic moment, Icarus makes the case that Putin used Olympic success to strengthen his political position before invading Ukraine by cutting from fireworks at the opening ceremony of the Sochi Olympics to explosions in Crimea. This edit is part of a montage that closes the film in which Rodchenkov, in a voice-over, describes his participation in the doping scheme while running an anti-doping lab as a form of Orwellian “doublethink.” Rodchenkov uses doublethink to rationalize his own behavior while the film frames the people who speak and appear in the images accompanying his narration—Putin, IOC President Thomas Bach, Marion Jones, Lance Armstrong—as corrupt and disingenuous. The sequence is a reminder that the state remains an essential component of the sports/media complex, even in the 21st century, and of the inseparability of sports and politics.

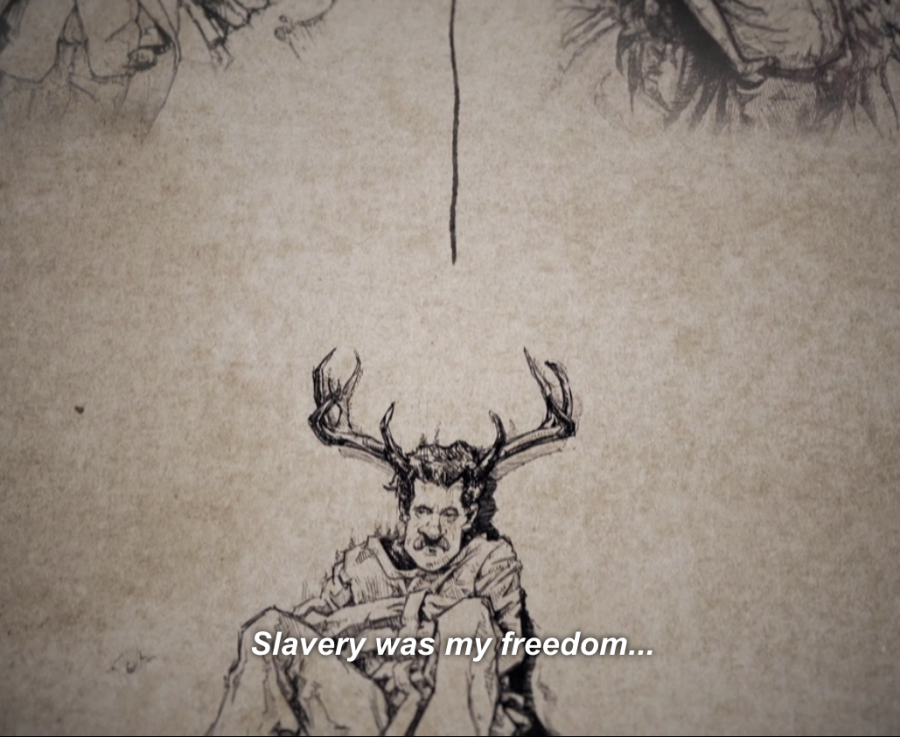

This montage ends with artist Sam Johnson’s ambiguous drawing of Rodchenkov, wrapped in a strait-jacket and thrown in a hole. Stag antlers, for some reason, sprout from his head along with caricatures of the opposing forces of doping and anti-doping. The image suggests a prisoner driven mad by the need to serve two contradictory masters. At the same time, the drawing also links the film’s narrative to a mad scientist’s twisted imagination, which as the film notes is Putin’s line of plausible deniability for the entire scandal: Rodchenkov has confused himself with the state.

The cryptic quality of Johnson’s drawing begs the viewer to scrutinize Rodchenkov’s motives. This would probably suit Rodchenkov, who appears to subscribe to the Henry Hill theory of how to live life in witness protection. From the moment he first appears, shirtless, on Fogel’s SkypeTM window, it is clear that the Russian has a love affair with the camera, a romance underscored on the soundtrack by the plaintive use of “À la claire fontaine,” a song about lost love, during his goodbye to Fogel at LAX. Rodchenkov’s wacky, gregarious performance works with the theorizing of doublethink to excuse his behavior, but his farewell to his wife is so abrupt by comparison that it is difficult for me not to imagine that his children probably see their father from a different angle.

However you decode it, the drawing, along with rest of the sequence, underlines the sarcasm of the film’s title: Icarus is not a story of hubris and ambition but an attack on the myth of sports. Former WADA chairman Dick Pound articulates this attack when he suggests that his investigation of Russia, “has the potential of affecting the credibility of all sport, and therefore the continued credibility of all sport. Why would I watch an event that’s fixed?” But one does not need to master doublethink to understand the limits of this rhetorical question. Fans watch sports not for fair competition but because they want athletes to be monsters who embody a range of supra- and superhuman qualities—strength, speed, endurance, purity, national identity—that give meaning to their own lives. This is an essential part of sport’s attraction and a major reason why the sports/media complex drives athletes towards doping in the first place. If you want to understand it, I recommend not 1984 but Debord’s ninth thesis in Society of the Spectacle: “In a world that is really upside-down, the true is a moment of the false.”

I saw the film’s form more as a runaway train or, who knows, as a metaphor for an athlete on steroids. The graphics were well done but seem to be in some other film. There is no doubt that Fogel and Rodchenkov had made some sort of bargain: perform in my film and I’ll get you out of Russia. In fact, that’s what was about, this rather privileged American using his wealth (my God, how many lawyers can one man afford?) to elicit a film from a Russian smart enough not only to run an invisible doping scheme but also smart enough to know when the state machinery he served was about to turn on him. And I believe that story. If Rodchenkov had a less interesting personality and fewer street smarts, there would have been no film – and ultimately no Rodchenkov. I don’t believe the 1984 business, which manages to make itself even less credible with the shots of Rodchenkov reading Orwell. The montages do get to be a bit much – not every word has to be illustrated. In fact, it would have been a much better film if it had been shot by a third party in pure “fly on the wall” style, letting the spectator make the connections. As is, I’m afraid the Academy loved it.

LikeLike

Encouraging Fogel to make another film would, I agree, be misguided. But the Situationist sports fan in me is ineluctably drawn to a fantasy of million kino-eyes gonzoing the sports media complex into oblivion. So I say give it the award! Complete the farce! Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Thanks to Travis and Robert for some reasoned discussion of this tragedy of a documentary: “I see Icarus as the Swamp Thing, vomited up from the ooze of corruption, chemicals, and media that constitute contemporary sports,” and I’d only add that the Oscars for documentary are part of this corruption! While the subject matter is certainly compelling (although confusing if not downright unintelligable in its current form), it’s stunning that the Oscars are considering an award for artistry to a product that is so poorly executed by artists that have no knowledge of the form.

LikeLiked by 1 person